In demanding a change in the treaty of the Pyrenees, in virtue of an ancient right called “devolution” [see footnote in From the French Guards to the King's Musketeers], Louis XIV entered into war with Spain in 1667 and marched on Flanders.

It was the beginning of a series of wars undertaken by the king of France.

The king could count on some precious assets in his wars of siege: to start, a powerful and well-organized army thanks to Louvois; secondly, a young military strategist and builder of fortresses named Vauban, and, finally, an elite corps of musketeers led by d’Artagnan.

The siege of Lille was to be an important test of this arsenal.

In 1667, Lille rivaled Lyon in number of inhabitants and houses. It was one of the largest, richest and most powerful cities in the Netherlands. Its conquest appeared ever more difficult in that it was fortified and had been commanded since 1665 by Philip Hippolyte Charles Spinola, Count of Bruay, a Spanish general who was reputed to be a great commander.

In 1667, Lille rivaled Lyon in number of inhabitants and houses. It was one of the largest, richest and most powerful cities in the Netherlands. Its conquest appeared ever more difficult in that it was fortified and had been commanded since 1665 by Philip Hippolyte Charles Spinola, Count of Bruay, a Spanish general who was reputed to be a great commander.

Odile Bordaz

In fact, Lille resisted for barely more than two weeks, during which d’Artagnan distinguished himself one more time (…) The French attack caused panic in the city. The 27th August, the people of Lille invaded the ramparts and disarmed the soldiers, thus forcing the Count of Bruay to capitulate (…) What remained was to face the Count of Marsin, who had rushed to Lille’s aid. In the night of 29th to 30th August, after leaving their camp at Denise, d’Artagnan and his brigade galloped behind Brigadier Count Henry of Podwitz. The French pushed back Marsin’s front lines, broke up its squadrons and provoked panic in the troops, who fell back.

Jean-Christian Petitfils

Louis XIV, already master of the art of spectacle, took particular care of the production surrounding his entry into the capital of Flanders. His brilliant escort of musketeers, with Monsieur d’Artagnan riding at its head, contributed largely. The king was perfectly aware of the event’s importance; the success of his program of integration for the city he had just conquered would depend in large part on the [event’s] perfect outcome.

Odile Bordaz

After the conquest of Lille, the Marquis of Humières was named governor of the city in 1668, but by 1672 he had fallen into disgrace.

Louis XIV could only entrust this city, with its strategic importance, to someone he could count on. And so, he once more called upon d’Artagnan.

During the past five years, the latter had fought in Franche-Comté and then had been sent to help quell an uprising in Vivarais. In 1671, he had found himself again in the position of jailer.

In this year of 1672, d’Artagnan was made Brigadier just as another war was heating up with the United Provinces of the Netherlands.

Without a doubt, he would have preferred to join the fight. But, as the king’s loyal servant, he took up his new post as military governor of Lille.

This time, the mission had nothing in common with the previous ones but, as for the arrest of Fouquet, it would prove to be of strategic importance. Unfortunately for d’Artagnan, it would not only separate him from the king and his musketeers, but would also deprive him of participating in several months of a long-awaited military campaign: the beginning of the war with Holland.

Odile Bordaz

Without a doubt, d’Artagnan would have much rather marched with the magnificent army of 120,000 men that Louvois, through patience and effort, had managed to assemble and had just handed over to Louis XIV. D’Artagnan was to miss out on the glory associated with the rapid conquest of Holland (…) which the enthusiasm of Louis XIV’s admirers succeeded in presenting as one of the most brilliant military operations of the century.

Charles Samaran

The great city of the North was at that time one of the strongest fortified cities ever built. Vauban completed major defensive works, wishing to make [the city], in his own words, «the eldest daughter of all fortresses”. The corner stone was laid in June 1668. Four years later, Lille already boasted the form of a regular pentagon, covered with a triple defensive line with entirely new bastions, demilunes and underground shelters.

Jean-Christian Petitfils

D’Artagnan enjoyed the same authority as the other provincial military governors. His principal responsibilities were to assure the security of the city, issue daily orders, make rounds to verify the service of the guard posts, authorize groups to raise funds, preside the council of war that judged offenses committed by the soldiers and decided on a suitable punishment (…) D’Artagnan’s was a particularly arduous task. Indeed, he found himself in a city where the French were not welcomed.

Stéphane Beaumont

D’Artagnan fulfilled his role as governor with rigor, but found that this job was not tailored to him.

His exclusion from the action on the front along with the meticulousness of the bureaucracy, which irritated him to no end, made his stay in Lille difficult.

Tales of quarrels between himself and the other men of the garrison figured in the letters he exchanged with Louvois…

D’Artagnan, with his irreproachable experience as a warrior, his aptitude for command, his universally recognized human qualities (…) certainly possessed a maximum of assets to carry out his mission. But one shouldn’t forget his unyielding Gascon temperament whenever he felt that his authority was the least bit contested.

Odile Bordaz

D’Artagnan, a genuine Gascon, did not have a very easy personality. Not tolerating any challenge to his authority, any lack of discipline, he did not hesitate to react severely whenever he felt the necessity (…) It was in Lille that he showed the full measure of his unyielding and authoritarian nature.

Jean-Christian Petitfils

Rivalries developed between d’Artagnan himself and other more or less important personalities. Did he not have to contend with a citadel commander who was, without a doubt, his rival, and with fortification engineers who boasted that they answered only to Vauban or the minister himself? Sources of continual offense, conflicts of authority (…) It should be pointed out that the correspondence between d’Artagnan and Louvois is rife with tales of dissent.

Charles Samaran

To tell the truth, the apparent difficulties within the government of Lille are perfectly explainable. The powers of the governors of the provinces and fortified cities had already been declining for a long time. Usually residing at the Court and making only a few, brief appearances in their territories, they had developed the habit of leaving the dirty work to their subordinates: the king’s lieutenant and the governor of the citadel. D’Artagnan was not of a kind with these grand seigneurs and those members of the court accustomed to purely honorific titles (…) he had no intention of abdicating to others the extensive powers conferred to him by his commission as governor general.

Jean-Christian Petitfils

No doubt to his considerable relief, d’Artagnan was relieved of his functions as governor general in December 1672.

A short time later, he was back on the battlefield with his king and his company, who were in desperate need of their lieutenant-captain.

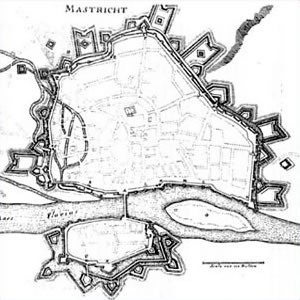

This time, the hostilities were centred on Maastricht, one of the most important strongholds of the Netherlands. In this siege, the English were allied with France under the command of the Duke of Monmouth.

During d’Artagnan’s stay in Lille, Jean-Louis Castera de la Rivière, given command of the first company of musketeers as sub-lieutenant, had encountered considerable difficulties from his men, from whom he was unable to gain their obedience. After the Holland campaign, a number of musketeers had managed to escape his authority and had not hesitated to desert and return to Paris (…) As soon as he returned to the Court, the lieutenant-captain retook possession of his company, and he would soon depart to join the king at his side.

Odile Bordaz

This time d’Artagnan was to command his company of Grand Musketeers directly. Paradoxically, he who had the rank of brigadier, that is brigadier general, and had been placed in command of several regiments of cavalry during the siege of Lille in 1667, would now only be commanding the 150 musketeers of his company—an elite, it is true. The second company was commanded by Monsieur de Montbron, who had distinguished himself at the capture of Lille.

André Laffargue

The 1st May 1673, Louis XIV, followed by the entire Court and by several thousand soldiers, set out once more on campaign. The task this time was to break the stubborn resistance of the Dutch who, the previous year, had preferred to open all their locks and keep part of their territory under water rather than give in to the French.

Jean-Christian Petitfils

The tide was turning. It was becoming very difficult. The emperor of Germany, the elector of Brandenburg, rushed to the aid of the vanquished. The Marshal of Luxembourg, taking advantage of the winter, had advanced all the way to The Hague; but the spring melt was forcing him into a rapid retreat. A vigorous reaction was called for. Turenne and Condé rose to the occasion and pushed back the enemies. As for the king, reuniting all his loyal troops, he resumed the offensive himself with the return of spring. The 1st May, he marched on Maastricht.

Armand Praviel

In 1673, Maastricht had a governor of French origin, Jacques de Farjaux, a very experienced warrior who had been serving in the king of Spain’s armies for some thirty years. [In] 1656 he had routed Turenne at the siege of Valenciennes. To defend Maastricht he disposed of some 65 pieces of artillery and a garrison of nearly 11,000 men, or twenty percent of the country’s armed forces.

Odile Bordaz

Maastricht was surrounded on 10th June 1673, and the siege began. It was to be a grand moment in the history of assaults on fortified cities. Indeed, for the first time Vauban made use of [a series of trenches parallel to the besieged fortifications], which would continue to be used by others after him with as much success.

Charles Samaran

It was to be the first great siege of his reign. Indeed, Louis XIV’s awareness of this was such that he ordered Colbert to send him an artist, noting “because I believe that something beautiful will happen.”

Jean-Christian Petitfils

On the 19th, the French artillery began their bombardment; the Dutch canons, while fewer in number, riposted vigorously. The artillery battle thus ensued over a period of five days, at the end of which the French command, considering the damage to be sufficient, decided to attempt a frontal assault.

André Laffargue

On the 24th June, the evening of the feast of Saint John, the attack was launched toward ten o’clock, the batteries on Mount Saint Pierre illuminating the sky with their joyous fire. Four battalions and eight squadrons of the King’s House, three hundred grenadiers and the first company of musketeers, led by d’Artagnan, launched an assault on Tongres Gate. This gate was protected by another demilune. It was first necessary to capture and hold this position in order to beat the enemy corps and break its lines.

Armand Praviel

Men fought in a loud clash just to gain a few inches of ground. Never in the annals of soldiery had one heard such a great number of explosions (…) The musketeers of the first company were in charge of the assault on the demilune, while those of the second company had the mission of attacking between the demilune and the salient. The combat was astonishing. Was it d’Artagnan, or was it Churchill who, under a hail of bullets, proudly planted the fleur-de-lis banner on the parapet? No one knows. All that matters is that in less than a half hour, we were in control of the demilune…

Jean-Christian Petitfils

On the morning of 25 June, the Governor of Maastricht counter-attacked in an attempt to retake the works lost during the night, which were of vital strategic importance. He sent in reinforcements and detonated a mine. The French guards who had taken over from the Musketeers were overwhelmed and began to retreat. The French thus risk losing the benefit of the night's fighting.

Odile Bordaz

It was through a heroic act on the part of the musketeers, just when the situation was hanging in the balance, that the stronghold of Maastricht was finally conquered.

This act proved fatal for d’Artagnan, for whom it was to be his final battle.

Who could one turn to in this moment of urgency? The lieutenant general in charge of the operation had only one thought, only one name: d’Artagnan! He sent orders for him to end his respite, forget his fatigue and return to battle. The musketeers and their captain were not the type of men to refuse combat. In a few instants they were ready, and they threw themselves into the assault with festive enthusiasm.

Armand Praviel

The captain of the musketeers was not on duty on Sunday 25 June, and he intended to rest from the exertions of the previous day. But when he learned of the sudden retreat of the guards, he left his guests and went immediately to Monmouth's quarters. It was then that he made the decision that was to cost him his life.

Jean-Christian Petitfils

What does d’Artagnan do? He approaches the famous barricade, where he is joined by the Duke of Monmouth and his “lifeguards”. It’s here that something happens that will be capital for what follows: a miscalculation made by the Duke of Monmouth. Rather than descending into the trenches in order to reach the demilune, the young duke, lacking the experience of the lieutenant-captain of the musketeers and in the interest of time, decides to cross in the open the passage separating the barricade from the targeted structure. D’Artagnan tells him that it would be foolish to so expose oneself to enemy fire and tries to dissuade him, in vain. The duke will not listen. And so, he charges forward, running, leading his men behind him. What can d’Artagnan do? Time is slipping away. He too charges forward, followed by his musketeers, as bullets and canon balls rain down on them.

Odile Bordaz

Thus, they went over the barricade with great momentum, followed by all their men at a running pace, their eyes fixed on the enemy position that greeted them with a thundering hail of bullets. After a few minutes of violent combat, the demilune was seized.

Jean-Christian Petitfils

It was on this occasion that Monsieur d’Artagnan was killed. The intensity of musket fire was such that even hail could not fall more abundantly: two musketeers trying to pick up Monsieur d’Artagnan were killed at his side, and two others who had taken their place and had given themselves the same duty, were killed in the same way next to their captain, without even having the time to pick themselves up… This battle went on for five hours in the light of day and out in the open, and one could almost say: “And the combat ceased due to a lack of combatants”.

Le Mercure Galant – June 1673 –

When the musketeers returned, their swords bent and bloody to the hilt, and when they counted themselves, they found that, in the two attacks, 80 men from the first company lay dead on the ground and 50 others were seriously wounded. What had become of the captain? He was missing.

Charles Samaran

The musketeers loved Monsieur d’Artagnan. When they saw that he had not returned, Saint Léger, first sergeant of the company, and a some other musketeers returned to the demilune to save their captain if there was still time. They saw him lying dead in the middle of the structure. Stricken with acute sadness, they dashed toward him and recuperated his body despite the fire from the enemy upon seeing them in the open.

A History of the Two Companies of Musketeers from 1622 to 1767.

When Louis XIV had arrived in person at the foot of the trench, the victims were counted: fifty officers killed or wounded, one hundred guards killed, three hundred wounded, including sixty musketeers. The survivors were overcome with grief on seeing their leader stretched out in the middle of the talus “biting the dust, recognizable from his weapons”. Near him lay the company’s silver banner.

Jean-Christian Petitfils

Thus fell d’Artagnan, who back in his native Gascony, had so wished to become a musketeer one day, now first among the musketeers in “the bed of honor” (…) He fell, not as a brigadier, but as a captain at the head of his elite company, in the most supreme act of battle: the assault!

André Laffargue

That is how he died, a death as simply heroic as his entire life, surrounded by the respect and the passionate devotion of his soldiers. It merits well the epilog from Viscount Bragelonne, where we see the illustrious musketeer expiring as he received the field marshal’s baton.

Armand Praviel

One last time, to save the day, d’Artagnan acted without having received an order, just as he had done during the siege of Lille. Did the king reproach him for it? How could he?! His faithful and devoted servant was dead. He himself recognized that he owed the operation’s success to his musketeers. Louis XIV mourned the lieutenant-captain of his musketeers. The very evening of his death, he wrote to the queen: “Madame, I have lost d’Artagnan, in whom I had the utmost confidence and who was good at everything.”

Odile Bordaz

The king spoke magnificently of Monsieur d’Artagnan and praised him in particular for being the only person who was able to win people’s affection even while doing things that weren’t exactly pleasant for them, meaning Monsieur Fouquet whom he had guarded with much precision and Monsieur d’Humières whose place he had taken.

Pellisson

His death provoked tears from the brave musketeers. There was not one who did not bitterly grieve his popular captain, “If one could die of sadness, in truth I would be dead,” wrote d’Aligny, “…Few would have taken the risk that he took, but the way things were, despite the accusations of members of the Court saying that his was the temerity of a young man, nevertheless the great merit of Monsieur d’Artagnan and the brave musketeers won Maastricht for the king…”

Jean-Christian Petitfils

The sorrow that d’Artagnan left behind him was immense and sincere. It was well known that, very much in the king’s good graces as he was, he had made, as Saint Simon would later report, a “considerable fortune”. People admired him because only his courage led him into danger and to his death, even as his station did not demand it of him.

Charles Samaran

D’Artagnan, whose courage

The most glorious advantage

Crowned all his exploits

Falls dead under a fiery barrage,

A blow that took the pomp

From those wearing the silver cross

And who marched under his yoke,

The King reels from this misfortune

With chagrin not at all common

And all his army in mourning

Bear this blow they cannot

Except by crying in their complaint:

D’Artagnan and glory share the same place of resting.

Juliani de Saint-Blaise

D’Artagnan was mortally wounded below the ramparts of Maastricht. A statue and a commemorative plaque stand where the lieutenant-captain of the first company of musketeers fell (…) One question remains: where is d’Artagnan buried? It was the custom in wartime to bury the dead, officers and simple soldiers alike, near the battleground itself, and this for obvious practical reasons. Very rare was the officer whose corpse was repatriated. And what of d’Artagnan? The question still haunts us: where does he lie?

Odile Bordaz

D’Artagnan died a hero in the same mystery that enshrouded his birth.

Whether in Maastricht or in Lupiac, a part of him is missing.

In his native Gascony, we can see his place of birth, but we don’t have a date.

In Maastricht, we have a precise date for his death, but we don’t have his body.

It is as if d’Artagnan’s body and soul had disassociated themselves in order to aid the novelist in his task of creating an eternal hero of legend.

D’Artagnan tried to pick himself back up. He was thought to have fallen without being wounded. Then, a terrible cry came from the assembled officers, stricken: the brigadier was covered in blood; the pale shroud of death was slowly rising to his noble face. Leaning on arms that extended from every direction to support him, he was able to turn his gaze, one last time, toward the citadel to see the white flag at the top of the main bastion. [His] ears, already deaf to the noise of life, could make out the faint drum rolls that announced victory. And so, gripping in his rigid hand the velvet baton embroidered with the golden fleur-de-lis, he lowered his eyes that no longer had the strength to look at the sky and he fell while murmuring strange utterances, words which had once had so much meaning on this earth and that now were only understood by this dying man: “Athos, Porthos, until we meet again! Aramis, forever adieu!” Of these four valiant men whose story we have told, only one body remained. God had reclaimed their souls.

Alexandre Dumas – The Viscount of Bragelonne