The swashbuckler, or “cape and sword” novel (Roman de Cape et Epée in French), made its appearance in France in the first half of the nineteenth century.

This literary genre, sometimes qualified as hybrid, combines the traits of popular and historical fiction with that of the adventure novel. As with popular fiction, the genre’s wide distribution was guaranteed by the newspapers of the epoch, in the form of the serialized novel.

By this medium, it reached a wide public seduced by stories built around clearly identifiable –some might say stereotypical—characters and paced by episodes full of dramatic ups and downs.

The swashbuckler belongs to the “historical” genre to the extent that the action generally takes place between the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries, at a time when disputes were regularly settled by duels. Indeed, this type of combat is the cornerstone of the roman de cape et épée, as the genre’s name indicates.

Finally, the genre is definitely one of adventure, as the action is what drives the story, with its panoply of intrigues, events and dangers that render the narrative exulting and thrilling.

Although the genre's kinship to other literary forms allows us to define it, we cannot ignore the singular originality of the swashbuckler. For, it is also a genre in its own right.

The appellation cape et epée , or swashbuckler, is the very sign of the genre's specificity.

But what gave all these historical adventure stories the generic stamp of cape et epée ?

The term itself is cloaked in mystery because, over time, it has lost all signification, or, to be more exact, all its significations. Today, it is easy to understand the role of the sword, or epée, in the appellation's origin. But what of the cape?

In order to fully understand, we must travel all the way back to the Spain of the seventeenth century. It is there that the term appears for the first time, fruit of an astute observation of the customs of the epoch, particularly those of the aristocracy. First of all, it is important to remember that Spain is the birthplace of the rapier, that light and easy to handle sword that allows its handler to strike with the point of the blade. Forged in the foundry of Toledo over many centuries, Spanish swords had a reputation as the finest blades in all Europe . Light, they could easily be worn on the belt, thus equipping the gentleman with a weapon that was at the same time readily accessible and effective.

The costume of the Spanish gentleman, in addition to the close-fitting jacket called the doublet, always included a rapier, the ensemble often enveloped by a cape. This last piece of clothing was not merely decorative; during combat, the wearer could furl the cape around his arm to deflect the blows of his adversary, while striking with his sword in his other hand. The Spanish aristocrat of the seventeenth century was rather touchy when it came to his honor, and he was quick to draw his sword when offended. The frequent duels even inspired the playwrights of the epoch, who created the Comedias de capa y espada , which presented an aristocrat clad in sword and cape as a main character.

The cape's role was even more subtle because it did not serve merely as a shield in combat; it was also the ideal apparel for concealment, notably that of the face. This characteristic did not escape the attention of the theater authors and it is certainly with the figure of Don Juan that the cape as concealment was used to its fullest on the stage. Indeed, the first Don Juan was from Seville , a character created by Tirso de Molina. In the play, entitled El burlador de Sevilla , the character uses his cape as a tool of disguise and deceit in order to take advantage of situations, and women in particular.

These Spanish nobles, clad in sword and cape in the very Catholic Spain of the seventeenth century were the ideal figures for inspiring an author's imagination. In fact, Spanish theater was quite popular in France during the seventeenth century, and authors like Scarron, Corneille and Molière also found inspiration in these Comedia de capa y espada . To learn more on this subject, visit our site www.don-juan.net

Parallel to its origins in Spanish theater, the expression cape et epée was also used in France to refer to a noble who was … penniless. It was commonly said of a gentleman without fortune that he only possessed “a cape and a sword”, the only remaining discernable attributes (costume and weapon) of a noble birth and noble education.

“It is figuratively said of a penniless second-born son from a noble house that he has nothing but his cape and epée.” Dictionary of the French Academy of 1694 .

Just how was this expression recuperated in the nineteenth century?

“If the expression is still used in the nineteenth century, it is for its picturesque and old-fashioned character or because, as it was employed as a generic label at that time, it added to the idea of poverty a certain connotation of panache that revived, in a positive light, the old locution.” Sarah Mombert, Duels en scène N°3 .

The first person to actually use the expression in the title of one of his novels was Ponson du Terrail, who published a book entitled La cape et l'épée in 1855.

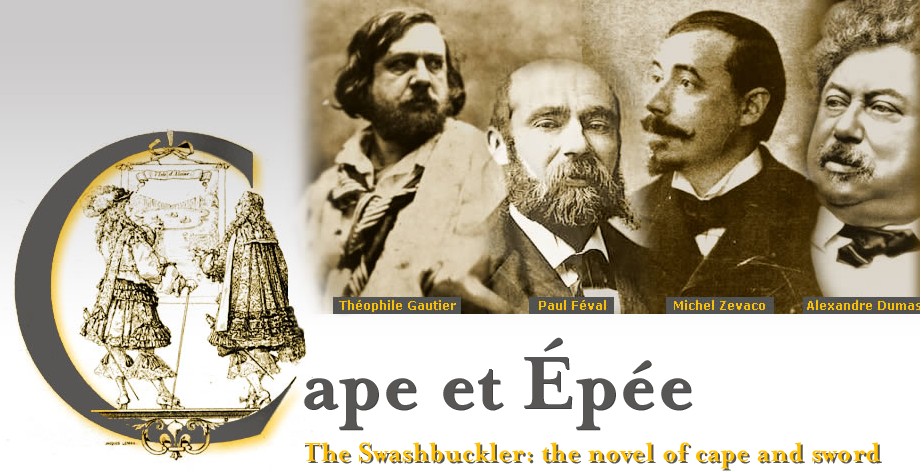

However, the genre already existed long before its appellation, and Théophile Gautier is universally identified as the father of the French swashbuckler. It is even rather droll to consider that the first hero of this testosterone-charged genre was actually a heroine: Mademoiselle de Maupin swaggered her way onto the literary scene in 1835.

Ten years later, Alexander Dumas gave the genre a little boost with his Three Musketeers . It was the main character of this novel – in the person of d'Artagnan —who was responsible for creating the archetype of the cape and epée hero. Dumas' narrative is in this way unique, in that it establishes the very codes that would become the genre's trademark.

In fact, successive authors would play with the double meaning of the appellation “cape and epée”. Invariably, the hero is a second-born son, or cadet , from the provincial lesser nobility, and ideally a Gascon . He begins his adventures penniless, his only possessions a cape, a sword and a humble steed… This is the case of d'Artagnan, of course, but also of other heroes such as Captain Fracasse or Pardailhan.

The cape as object of dissimulation is reused in numerous narratives, where we find the theme of the double or the mask. Paul Féval's character Lagardère, for example, disguises himself as a hunchback in order to achieve his ends. Scaramouche and Captain Fracasse are pseudonyms that allow their owners to accomplish their mission, protected by the mask of an assumed name. Similarly, Gautier's Mademoiselle de Maupin disguises herself as a man. And who can forget the famous Zorro: the noble Don Diego de la Vega by day, masked hero by night?

But in all these novels, in the end, one half of the original term cape and epée remains a tangible object, while the other has become a symbol. The epée, or sword, remains as a shining reminder of all those duels, all those final confrontations that were the denouement of each story.

As for the cape, it is often forgotten next to the brilliance of the sword. And yet, the two objects cannot be disassociated from each other because the cape, too, gives a certain panache to its wearer. It is elegant as it unfurls in the heat of action, it disguises, and it flutters in the wind. For a hero like Zorro, the cape is as much his trademark as are his mask and sword.

It is interesting to note that the English term for the cape and sword genre, swashbuckler , is not quite as noble in its connotations. The term arose in the sixteenth century and is derived from the verb to swash --meaning to swagger, that is to march about with an insolent air or to boast noisily—and buckler , another name for the shield with which the swordfighter parries his opponent's blow.

The vision of the strutting, shield-thumping English swashbuckler contrasts colorfully with that of the French hero ensconced in his flowing cape, and it speaks volumes on the differences between the two cultures!

Whether we call it the swashbuckler or cape and epée novel, the genre enjoyed an instant success in the nineteenth century, to the extent that it falls within the framework provided by the Romantic Movement.

If the swashbuckler stands apart among all the other historical novels of its time, it is because it reconciles the individual with history and gives him a heroic role, in the same line of the romantic hero of the epoch.

The hero of cape and sword

Who is this figure that has inspired the collective imagination? What is it in his personality and in his appearance that has seduced so many readers, from the age of five to one hundred and five?

First of all, our hero is a nobleman; whether from the high or lesser nobility, or an aristocrat who is ignorant of his noble origins, it doesn't matter. He is still a noble.

And because he is a nobleman, he wears a sword and he knows how to use it. He also embodies the values of the aristocracy in that he is never afraid to answer a challenge or defend his honor. And if that is not enough, our noble often finds himself in the service of the most important figures in the kingdom, even the king himself. And through this service, he takes the reader with him into a world that is as attractive as it is exclusive: that of the Court, salons, balls, palaces and chateaux.

For the general public this constitutes a real voyage into a strange universe: that is a dream world of luxury and sophistication. With the hero of cape and sword as his guide, the reader penetrates, as if by a secret window, into the inner sanctum of high society, where he discovers their schemes, stories of deceit and of vengeance as well as generosity of spirit.

The hero is often accompanied by friends or comrades in arms, who take on complementary roles. His comrades have the very qualities (or defects) that complete those of the main character. These supporting characters also bring with them their friendship and their solidarity which allow the hero to face and conquer his foes. They surround the hero with their benevolence and their protection.

And, of course, the hero of cape and sword is always young, jaunty and, if not stunningly handsome, at least charming and seductive. He is shrewd, intrepid, full of courage, always ready to come to the rescue of some princess, never shying away from the most foolhardy of risks, never daunted by the impossible. His is the side of justice and Good. Thanks to him, the evildoer is always punished.

Even if this portrait appears just a little stereotypical, each hero is unique in his own way.

Every hero of cape and epée has his own personality, a strong character, a sense of humor and an often delicious way with words. What is more, the hero develops and constructs his identity throughout the narrative, and the reader follows the main character as he grows in maturity or in fame. Like any man, the hero's path is studded with trials that one could qualify as a rite of initiation, often a passage from adolescence to adulthood.

The sword, or epée , is the logical accoutrement of this passage, as wielding it requires certain psychological and physical values. Hence, the swashbuckling hero becomes a model for the young reader in particular, who identifies with the character, exchanging the latter's trials for his own. He represents everything that the reader only dreams of doing.

From the most perilous adventures to the most improbable love affairs, the reader can live vicariously through his hero, but without feeling inadequate because the historical context creates a necessary distance.

The historical context

The action of the French cape and epée novels takes place in the period spanning from the end of the sixteenth century to the beginning of the eighteenth century, that is, from the birth of Louis XIII to the death of the Sun King, Louis XIV. This was the grand epoch of the rapier and of sword-fighting, notwithstanding the prohibition against dueling at that time.

With its kings and cardinals (Richelieu and Mazarin) who put their mark on France , a royal Court full of intrigues, and nobles pitted against a monarchy that was becoming more and more absolute, this period was an ideal backdrop for a tableau rich in adventure.

And the authors of cape and epée did not hesitate to take advantage of this backdrop. More, the serialized novel, with its episodic chapters, allowed the writer to spin a story full of cliffhangers, making the narrative more and more thrilling with each episode.

Of course, the writer adds a heavy dose of fantasy to his interpretation of history. True, the reader will find real, historical events, with detailed descriptions of people, places and customs. But, in the end, history is an actor in the adventure, just like the characters, whom the writer manipulates to serve the purposes of his narrative. The Three Musketeers remains the best example of this re-writing of history, as Dumas decided to transpose his hero, an actual historical figure, into an era that was not his own.

Duels

Without them, the swashbuckler would not exist. The duels' role is primordial. They enhance the hero's image, placing him in a permanent state of danger and then allowing him to conquer his foes who, often, are the very embodiment of Evil. In confronting his adversaries in hand-to-hand combat, the hero shows that he is not afraid to risk his life for the cause of Good. This Manichean struggle is an indispensable element in the narrative.

“In the duel, a force that is very often that of evil is eliminated, albeit symbolically; for, if the forces of evil won duels, then the cape and epée novel would be fail to deliver on its ideological vocation. With the duel, too, we are at the heart of the writer's problematic: what is the event that will make the rhythm ever more breathless, that will keep the reader's interest and produce a paradoxical surprise every time? Because, we know what will happen, but we are always happy to read it anyway. What device will satisfy, at the same time, the imperatives of a logical narrative and that of the characters? It is the duel.” Gerard Gengembre .

And so, the genre presents us with numerous duels that repeat themselves each time the hero encounters enemies that he must combat. To add a little suspense, the latter can be better duelists than the hero, putting him in a position of weakness and forcing him to employ courage or shrewdness to avoid defeat. In this combat in close quarters, the reader is spellbound, hanging on each thrust of sword.

As a general rule, the duels should be sufficiently different each time in order to keep the reader interested. And so, they push the writer to be more creative, which is how Paul Féval created his now-famous “secret weapon from Nevers”.

Too, the duel brings with it an element of the illicit, which makes it even more exciting. We shouldn't forget that dueling, while commonplace in d'Artagnan's time, was forbidden and severely punished. In many swashbucklers, the hero often has to find a secret venue for his duel, which also adds to the suspense.

This element was still very present at the time these novels were written. For, duels still existed –illegal as they were—in the nineteenth century. For a reader of the epoch, the duel was not just some fancy technique from a distant time. The reader of the romantic era recognized and felt the duel's value and the dangers associated with it in a way that the twenty-first century reader cannot.

Indeed, for the gentleman of the nineteenth century, swordsmanship was still fashionable. The famous authors of the cape and sword genre were themselves duelists and even frequented the arms rooms of Paris , still plentiful at that time. The most famous arms room of that time was that of Augustin Grisier, where one could encounter Alexander Dumas, Théophile Gautier, Charles Nodier, Georges Sand or Paul Féval (who came as a spectator to glean ideas for his novels).

In the twentieth century, the novel of cape and sword would give birth to the film genre of the same name. In fact, it was one of the first genres to be adapted to the screen, because its well-established codes –struggle between good and evil, an easy-to-follow storyline, duels and quick-paced action—lent themselves easily to silent film.

And for film in general, the swashbuckler genre is a real gift with its bright colors, fanfare and flamboyance. But, it is still the duel that conquers all the spectators' hearts. In these films, the duel sequences become a part of history. Who among us doesn't remember one of these famous duels seen in childhood? The genre seems inexhaustible and cinema regularly reinvents the swashbuckler by imagining sequels (The Daughter of d'Artagnan or The Mask of Zorro) or by reprising great classics (The Three Musketeers or The Iron Mask).