The episode of the Fronde enabled Mazarin to test his men’s loyalty and effectiveness. And he did not show himself to be ungrateful to those who had served him well. As early as his exile at Brühl, he had considered bringing d’Artagnan into his Guards, but the latter would have to wait some time to see the promise become a reality.

On the 23rd April 1651, Mazarin wrote to Lionne regarding Marshal Gramont, field master of the regiment of the French Guards: “The Queen having once promised d’Artagnan a post of lieutenant in the guards, I would like to assure that if he (the Marshal) mentions this to Her Majesty, he will still find her so disposed.” Unfortunately, as a post of lieutenant was not available for the moment, d’Artagnan only received more promises, which was all that Mazarin could give.

Jean-Christian Petitfils

Without a doubt, Anne of Austria appreciated d’Artagnan’s courage and devotion, and the fact that he was an underling of His Eminence certainly gave him even more esteem in her eyes. Due to a lack of vacancy in [officers’] commissions, d’Artagnan would have to wait awhile for this recompense he so richly deserved.

Odile Bordaz

One year later, in April 1652, d’Artagnan finally obtained his commission of lieutenant, but in conditions that were far from comfortable.

He (d’Artagnan) was rewarded with a lieutenancy in the guards, in the company of Vitermont, as a replacement for the Chevalier of Passy, fallen at Gravelines. Moreover, the welcome that the regiment reserved for him, after so many years of absence, was rather cold. The manuscript from the Historique des Gardes added this sibylline commentary to the mention of his nomination: “He met some difficulties in the regiment due to the affection that the officers had for Cartgrès, who was the senior-most ensign.”

He (d’Artagnan) was rewarded with a lieutenancy in the guards, in the company of Vitermont, as a replacement for the Chevalier of Passy, fallen at Gravelines. Moreover, the welcome that the regiment reserved for him, after so many years of absence, was rather cold. The manuscript from the Historique des Gardes added this sibylline commentary to the mention of his nomination: “He met some difficulties in the regiment due to the affection that the officers had for Cartgrès, who was the senior-most ensign.”

Jean-Christian Petitfils

The regiment that [d’Artagnan] had just taken command of had been expecting one of its own to become its leader: Cartgrès, the senior-ranking ensign and a man of experience and courage, who had joined in 1646. [He] hoped to receive the first commission of captain available, as his superiors had promised him after his heroic actions at the siege of Armentières, where he “had found himself commanding six companies of guards (…) in the absence of all the officers. Unfortunately for him, Mazarin had made his own promises that he intended to keep.”

Odile Bordaz

D’Artagnan served Mazarin again in 1653 and right up until the end of the Fronde. The cardinal appointed him Captain of the Royal Aviary, a commission which was to help improve his financial situation.

It was in 1654 that d’Artagnan reintegrated the Guards, just as war with Spain was starting up again along the Flemish border.

After so much heroic effort, it was a time for recompenses, recompenses rather varied and that would appear strange to us today. Notably, d’Artagnan was named Captain and Guardian of the Aviary of the Tuileries Palace, though Colbert was also granted the same commission.

Armand Praviel

Finally, in 1654, we find d’Artagnan returned to his regiment and the warrior’s life he wished for; from then on he could “march with the King’s army”.

André Laffargue

In 1654, after having accompanied the king to Reims for his coronation ceremony, the regiment marched upon the walls of Stenay, which was overrun the 9th June and capitulated on the 6th August after one month of trench warfare. A number of assaults toward the end of the siege proved deadly, and though d’Artagnan was not among the dead, he did not escape unscathed.”

Charles Samaran

In the meantime, taking advantage of the fact that the French army was bogged down at Stenay, the Spanish attempted to retake Arras. And so, as soon as Stenay had capitulated, the 6th August, the French army, under the command of Turenne, marched to the rescue of Arras. Despite the efforts of Condé (who had changed sides), the Spanish trenches were overrun and the enemy army was forced to retreat. Had d’Artagnan recovered enough from his wounds to return to Arras a second time?

André Laffargue

The following year, he was at the siege of Landrecies and that of Saint Ghislain, where the guards were victorious on the 25th August, the feast day of Saint Louis, and offered [their conquest]as a present to the king. In the meantime, d’Artagnan had come up in the ranks. In the month of July 1655, apparently, he received, thanks to the support of His Eminence, the commission of captain of the Guards in the Fourille company, a commission for which he paid 80,000 pounds.

Odile Bordaz

D’Artagnan had dreamed of becoming captain for too long to balk at these terms. In order to amass this sum, he had to sell his commission of lieutenant to a certain Frassy, ensign in the guards, and then that of Captain Concierge of the Aviary to Monsieur d’Estrades, governor of Mézières, as well as the right to pass the post on to his son. With all the figures added together, he still lacked 4,000 pounds. That was the amount of the loan Colbert agreed to give to him, at Mazarin’s request, on 13th January 1656…

Jean-Christian Petitfils

And so it was a the head of his own company, in the army led by Turenne, that he participated in the ill-fated siege of Valenciennes in June 1656: defeat for the royal army, the loss of one of d’Artagnan’s comrades in arms in the person of Captain de Vitermont, under whose orders he had served and whose last words he received. (…)

In 1657, the Guard companies fighting in the armies of Turenne and La Ferté participated in the sieges of Cambrai, Montmédy, Andres, la Mothe-au-Bois, Bourbourg.

Odile Bordaz

In 1657, Mazarin reconstituted the famous Company of Musketeers that he had dissolved in 1646. The better to control these musketeers, the cardinal appointed his own nephew, Philippe-Julien Mancini, Duke of Nevers, as commander. With little taste for the soldier’s life, the duke deferred to his sub-lieutenant, Isaac de Baas, who would soon be replaced by d’Artagnan.

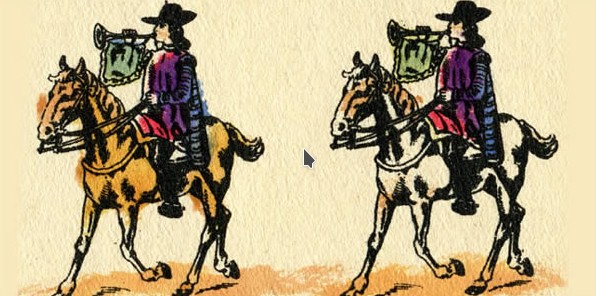

Between the end of 1657 and the beginning of 1658, the musketeers worked to reinforce Mardyck, which the Spanish did not dare attack (…) From there, they marched to Dunkerque in May. They had not been there for very long when, Baas having resigned his commission for health reasons, d’Artagnan, who was also stationed under the walls of Dunkerque with his company of French Guards, was called to take his place.

Charles Samaran

Isaac de Baas “was already old and all used up from the fatigue of war”. No sooner had he given up his commission of sub-lieutenant than the Cardinal passed it on to d’Artagnan. This is what he would have liked to have done upon the company’s creation if he had not had obligations toward Baas. Thus, the Cardinal’s choice, in light of so many possible candidates for the sub-lieutenancy of the musketeers, appears to be a confirmation of the high esteem in which he held d’Artagnan. More, the fact that he made the latter the tutor to this nephew, whom he so ardently wished to turn into a real leader, was proof that he considered [d’Artagnan] to be his most accomplished officer.

André Laffargue

In the days that followed, the musketeers, back on their horses, entered Dunkerque, Gravelines, Oudenarde, Ypres with trumpets blaring; no obstacles remained in their path. The following November, Mazarin and Louis de Haro signed the Peace of the Pyrenees on the Isle of Pheasants, in the middle of the Bidassoa estuary (…) Our musketeers, like all the good soldiers of France, had the right to rest.

Armand Praviel

D’Artagnan was barely forty years old at that time, and his title of sub-lieutenant of the King’s Musketeers gave him a certain stature (…) And so began d’Artagnan’s Parisian life, divided between military duties and social obligations.

Charles Samaran

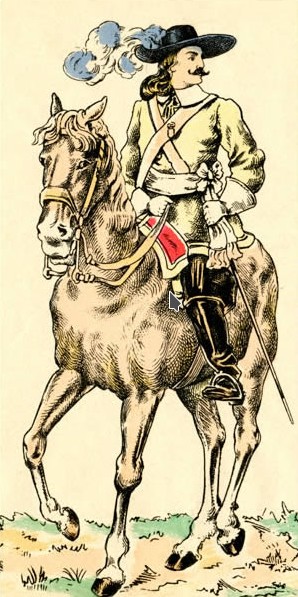

Finally recognized, now more than ever a symbol with his azure tunic blazoned with the gold-braided silver cross of the Grand Musketeers, the “forty-something” that d’Artagnan had become had managed to transform his fate as a younger son of Gascony into a beautiful success story…

Stéphane Beaumont

D’Artagnan’s entry into the musketeers was to bring him closer to Louis XIV. Mazarin’s death brought them closer still, as the king in turn took d’Artagnan as his right-hand man.

His military career was thus punctuated by missions of state, including a term as the jailer of Fouquet and, more briefly, of Lauzun.

But these missions would not distract him from his commitment to the First Company of Musketeers, of which he was the de facto leader while Philippe Mancini was abroad.

This was to garner disapproval on the part of Colbert, whose own ambitions were being stoked by the creation of a second company of musketeers, Mazarin’s ex-company.

Yet, d’Artagnan’s position was to be consolidated by his command of the first company, called the Grand Musketeers, even if he didn’t enjoy the title. Meanwhile, Colbert’s brother took command of the new company, called the Lesser Musketeers.

Although the Fouquet incident could have compromised his ordinary duties, d’Artagnan kept control of his company during this period, continuing to manage the organization, recruitment and discipline thereof without any interference other than that of the king.

Jean-Christian Petitfils

During the month of January 1665, while d’Artagnan was struggling through the snowy roads of Pignerol, Colbert obtained the commission of lieutenant-captain of the second company of musketeers for his brother, Edouard-François Colbert de Vandières, count of Maulévrier, [a position] until then occupied by Monsieur de Marsac (…) Jean-Baptiste Colbert had no doubts for his brother’s future; he saw him leading both companies together.

Odile Bordaz

D’Artagnan was only sub-lieutenant of the first company at that time. Would Maulévrier therefore have seniority over him?

Charles Samaran

The King didn’t want him. He decided that d’Artagnan, whom he soon intended to name lieutenant-captain in place of the Duke of Nevers, would be given command of the Company of the Grand Musketeers, as if he already had the rank of lieutenant-captain. This was tantamount to giving d’Artagnan command of both companies.

André Laffargue

While waiting for the resignation of Mazarin’s nephew, the post of lieutenant-captain was disassociated from its responsibilities, which were expressly conferred to the sub-lieutenant. As early as the 16th January, Le Tellier had the pleasure of explaining this new organization to d’Artagnan, who was still struggling in the snows of Pignerol: “I assure you,” he wrote in closing his letter, “that you will never have a stroke of good luck the like the one I wish for you.”

Jean-Christian Petitfils

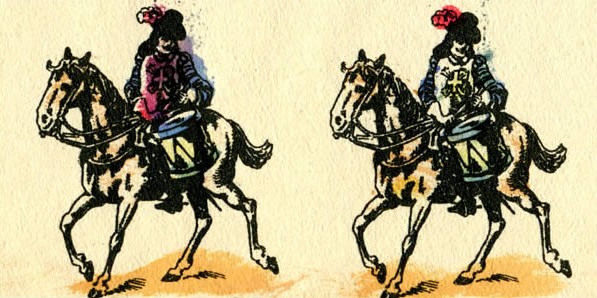

However, the coexistence of the two companies, also called the Black Musketeers and the Grey Musketeers, was not entirely peaceful. Maulévrier and d’Artagnan had two very different visions for their fighting corps.

The most up-and-coming gentlemen who wished to serve the king joined the ranks of the black musketeers in great numbers because they were commanded by the brother of an important person. D’Artagnan –whom we should put in his place—allowed more than a little jealousy to take hold of him. He realized that his new colleague was constantly trying to undermine him by always equipping the men in his troop more magnificently.

Jean-Christian Petitfils

More than ever before, d’Artagnan tried to make his company shine. He had to struggle against the rich Maulévrier who, since his promotion in grand pomp in the courtyard of the Old Louvre, had been busy decking out the musketeers of the second company. The price for d’Artagnan’s own self-worth was to be very expensive, for which he reimbursed himself with money from the extraordinary war fund.

Charles Samaran

Monsieur de Maulévrier’s desire to best me and to establish himself with His Majesty at my expense made him invent a thousand different kinds of expenses with which he thought neither I, nor my musketeers, could compete… He wanted (his company) to have golden tunics, which cost I don’t know how much money; and as it was unfair that he try to put me in check, I did everything I could to stop him.

Courtilz de Sandras

Mémoirs of Monsieur d’Artagnan

A real competition, not only for luxury and magnificence but also for privilege, had taken hold of the two companies and their respective leaders (…) For his part, d’Artagnan, far from admitting himself beaten, took his revenge by forming within his company an elite cavalry, the best in the kingdom, a riposte that would thrill Louis XIV.

Odile Bordaz

In the spring of 1665, France was allied with the Dutch, who had just entered into a war with England. Accordingly, Louis XIV sent an expeditionary corps to help the Dutch.

This force included a large detachment from the King’s House, to which the musketeers belonged. It was an opportunity for the two competing companies to fight side by side on the battlefield.

Despite a number of disciplinary problems within the French army, the first company exhibited exemplary behaviour, for which the king commended d’Artagnan on a number of occasions.

Monsieur d’Artagnan, I have received the roster of my company and saw with great satisfaction that it is complete. Be ever vigilant to maintain it in good condition, and do not forget to make it do drills in order to make the new musketeers as well coordinated as the others.

Letters from Louis XIV to d’Artagnan

16 November 1665

I could not hope for more zeal from my first company than that which I have learned she exhibited during the transport of the bundles from Loken. This confirms more and more my faith that she [the company] will never find beneath her any service I ask of her.

Letters from Louis XIV to d’Artagnan

25 December 1665

he king was preoccupied by the coexistence of the two companies. He, who knew well d’Artagnan’s sensitivity and the reasons for his irritation, urged him to show patience and moderation, while hinting at the rewards that he had in store for him: “I am totally convinced that my first company of musketeers behaved in an orderly way. In addition to the faith I have in what you have written me, all the letters from the army have confirmed the same thing to me and also remark that there is no other [company] like that in the services. The only thing to do is to preserve this good behaviour so that I might always be satisfied with the company and, principally, with you who should rest assured of the continuation of the tokens of my esteem when the occasion arises.”

Odile Bordaz

And indeed, the king did continue to show his benevolence toward d’Artagnan. First, he named him Captain of Hunting Dogs (for the deer hunts), a commission that the latter gave up rather quickly. Better, he appointed d’Artagnan to succeed the Duke of Nevers as Lieutenant-Captain of the First Company of Musketeers in 1667, a commission coveted by many others.

The ministers supported their preferred candidate. Naturally, Colbert wanted [the commission] for his brother in order to reunite the two companies under a single command. He was in any case personally opposed to giving it to d’Artagnan, whom he had not forgiven for his attitude judged as too independent during the trial of Fouquet. Nevertheless, it was to [d’Artagnan] that the king gave this gift.

Jean-Christian Petitfils

On the 22nd, the King had assembled the companies of his Body Guard with the First Company of Musketeers on the plain of Ouilles. [Monsieur] d’Artagnan took over the commission of Lieutenant of the latter, position vacant following the resignation of the Duke of Nevers; some other officers having also been appointed, in the afore-mentioned company as well as in the Body Guards, in such a way as to show to what point His Majesty knows how to reward the merit of those He chooses to honor.

La Gazette de France

28 January 1667

I saw Monsieur d’Artagnan, to whom the king had given the commission of lieutenant-in-chief of the musketeers upon the resignation of Monsieur de Nevers, notwithstanding the fact that Monsieur Colbert does not like Monsieur d’Artagnan. He greeted me profusely. The king’s conduct in his favor is surprising; he knows that he is a friend of Fouquet and an enemy of Colbert.

Journal of Olivier d’Ormesson

Having become lieutenant-captain of the mounted First Company of Musketeers serving in the king’s guard, receiving a salary of nine hundred pounds per month (adding to the stipend of six thousand pounds per year granted by the king), d’Artagnan held one of the most coveted commissions in the kingdom, the most beautiful according to Colbert. The son of Castelmore had become one of the known and respected seigneurs of the Court. One frequently addressed Charles de Batz de Castelmore as “Monsieur the Count”, for whom this royal and stately recognition was materialized in the thenceforth official title of “High and powerful seigneur, Monsieur Charles de Castelmore, Count d’Artagnan”.

Stéphane Beaumont

One must admit that d’Artagnan knew how to brilliantly extract himself from the most delicate situations (…) What the king appreciated the most in him, aside from his obvious qualities as a warrior, was at the same time his frankness –which the great difference in their ages permitted—and his loyalty in every trial (…) He who had learned very young to suspect everyone, knew that he could totally count on d’Artagnan, because the latter was ready to lay down his life for his king (…) It is important to be aware of this state of mind in order to understand Louis XIV’s attitude toward d’Artagnan and the brilliant career that the musketeer had during nearly half a century, managing to overcome all obstacles without ever knowing the slightest disgrace.

Odile Bordaz

Not long after, in May, he was elevated to the rank of general officer, as brigadier of the cavalry, rank which would accompany him on campaigns. Because, in this month of May 1667, war had started up again with Spain, Louis XIV having seized Flanders in virtue of his right of succession, the name that would be given to this war (1). The musketeers, under the command of d’Artagnan, followed the King to the sieges of Lille, Tournai and Douai.

André Laffargue

And so, began the great war campaigns of these two companies of musketeers finally reunited by the king.

(1) known as the War of Devolution in France, waged because of a dispute over the succession to Philip IV of Spain, who had just died.