Courtilz de Sandras was the first to take an interest in d’Artagnan’s life (he had served under the famous musketeer), and he wrote a three-volume apocryphal memoir of the latter.

Without Sandras, Dumas would never have written The Three Musketeers .

Strangely, this seventeenth century author spent most of his life in anonymity and published most of his writings illegally in Holland.

And this is why so few readers have heard of him. He has been attributed works that he never wrote while never receiving credit for the ones he actually did write.

He was one of those “free” authors, who lived on the margins of their epoch, and mixed different literary genres, and whose specialty was a kind of historical fiction based on fact.

Critics have always given him a bad time, and the fact that he dappled outside of traditional literary venues made him an easy target.

We can even read some rather virulent testimonies about him, for example:

Bayle : “He is someone who wants to be read and who, to keep his readers, speaks of things as an eyewitness, though he has never left his room.”

Voltaire : “ We only mention his name here to warn the French, and especially foreigners, to what point they must not put their faith in all of these fake memoirs printed in Holland . Courtilz was one of the guiltiest writers in this genre. He inundated Europe with fiction that he called history. It was shameful that a captain of the Champagne regiment should go sell his lies to the booksellers of Holland . He and his imitators, who have written such libel against their own country, against great princes who do not deign to avenge their honour and against citizens who cannot avenge theirs, have deserved the public's loathing.”

Jean de Bernières: “A rather pathetic character, as it happens, venial and without shame who, when pressed, refuted his own calumnies: a disloyal soldier and rebellious subject of his prince; fled to Holland in order to defame his country in ease, sent back to France for having abused his foreign host's hospitality; always ungrateful to someone, forever a fugitive somewhere, until the Bastille, whose secrets he claimed to have divulged, finally closed its doors behind him and reduced him to a prolonged silence. It seems that one should not give credence to anything written by his pen. His desire was to excite and satisfy the basest curiosities. In making a speciality out of his apocryphal Memoirs, Sandras abased, to the point of reprehensible speculation, a literary genre that ought to be tantalizing without prevarication and sensational without being scandalous.”

Not a reputable character, judging from these testimonies. But is there truth to this testimony?

Who was Courtilz de Sandras? Where on the continuum between reality and fiction can we situate this man who wrote history in the form of a novel? What should we retain of his Memoirs of Monsieur d'Artagnan , who went on to be reviewed and corrected by Alexander Dumas before being transformed into the literary triumph that we know?

His life

Gatien Courtilz de Sandras was born in 1644, probably in Paris, son of the chevalier Jean de Courtilz, seigneur of Tourly, and Lady Marie de Sandras. His was a long line of aristocrats. His parents, though certainly not very wealthy, came from a family of considerable notoriety and were able to give their son a decent education, which was to serve him later. Although he exhibited early on a certain relish for a life of letters, he would follow the path of other young men of his time: that of the army.

He must have joined the army in 1660, judging from this letter where he refers to Louis XIV: “Since the age of fifteen years, I, yours truly, have not stopped serving in his armies…” Indeed, this matches the average age at which young men took up military service. His family managed to get him into the First Company of Musketeers, a sign that they must have had some connections in this reputed and coveted corps. He was therefore a musketeer in the same company that was officially commanded by the Duke of Nevers, but of which d'Artagnan was already the de facto commander.

In 1667, he entered the Royal Foreign Regiment, in the cavalry with the rank of standard-bearer and he fought in the Flanders campaign, serving under Turenne. After the decommissioning of the regiment at the campaign's end, Courtilz de Sandras went back to civilian life for nearly four years. He lived in Paris and at Tourly, which belonged to his cousin, and in these two places he made acquaintances that might have served as inspiration for his future writing.

In the meantime, probably in 1664, he married Marie Despied, who gave him one son and one daughter. Unfortunately, his wife died in 1671, leaving him a widower at the age of 27.

In 1672, Courtilz went to war again and was given command of a company in the regiment of Beaupré-Choisieuil as captain of cavalry. We don't know if he participated in the war against Holland , but he was certainly involved in military operations in Catalonia in 1675, then in Alsace and, finally, in Roussillon.

His military career ended in 1679, probably during the dissolution of a number of companies that occurred in that same year. He was 35 years old at the time.

“He had already been preparing, for some time, what one could call his re-adaptation to civilian life: he had married and, through a few publications, he had entered into a literary career.” Jean Lombard.

Indeed, in 1678, he married Louise Panetier, a fairly wealthy bourgeoise. As he was in debt, this seems to have improved his financial situation. We don't know if this same need for money is what pushed him to write, but his first four books were all published during this same time period. The titles published were: An Account of Events in Catalonia , Stories of Love and Gallantry, New Anthology of Letters and Courtly Letters with Their Responses on Various Subjects and Account of Events in Flanders and Germany . Courtilz published these works officially and with the support of Monsieur de Bezons, a counselor of State.

Then, he decided to devote himself to adventure novels, but in a clandestine way. He lived in Paris and Holland , where most of his books were published by editors working under assumed names, as was the case for all literature forbidden in France .

He chronicled scandals at the same time that he wrote political works. In 1685, he embarked on a new path, that of biographies of famous people, such as The Life of the Viscount of Turenne . This new orientation would become his “milieu of predilection”.

For several years, we follow him from one place of residence to another, perhaps even across a number of European countries. It seems that he even took up residence in Sedan , which was a hub for the traffic of banned books, all printed in Holland . Obviously, all these books were seized.

He also threw himself into “journalism”, founding the Mercury of History and Politics in 1686.

In 1689, he acquired a property called “Le Verger”, situated near Montargis, which added to the list of his various residences.

He was not yet troubled for his secret literary activities, but he regularly used his connections to intervene on behalf of his book-seller friends accused of distributing forbidden books.

Courtilz de Sandras was taking risks, however, because he planned to publish a great work on the king's life entitled, The Life of Louis XIV, King of France and Navarre, alias Louis Dieudonné and Louis the Great , and in which he wished to tell all, as he indicates in a draft preface:

“I am not afraid that people will say that I have been bought, as happens to most of the writers of our century, and, indeed, would one give them money if they didn't know how to flatter? It's the price given in exchange for the incense that they offer in every meeting; but I find that this money is badly spent, for are there not other men who write in their study and who, working only for their reputation, are incapable of being corrupted? And so I hope, though I have not yet written any works to pave my way to public esteem, that people will make as much of this story as they once did of Boileau and Racine. It's not that I wish to attack their ability, and the King's choice is proof of their merit, but I would like to say that we should suspect what they give us, as their work is brought to Versailles notebook by notebook and wouldn't be destined to fame if it didn't first pass through this filter. This said, it is the King himself who is the proof-reader, hence one can imagine what to expect from such a work…”

This imposing and dangerous book would never be completed.

His writing is also singular in that he was able to write, in quick succession, a book and its refutation, certainly with an eye to increasing his profits. This proves to be a stumbling block when we try to become more familiar with the writer, even more so when we consider that his writings were not necessarily all signed by himself.

Courtilz was obviously in need of money. On the one hand, he had installed his wife and his numerous children at Le Verger. Although it seems that he took a real interest in his offspring and in family life, it was his wife who oversaw the agricultural activities of the manor. At the same time, he earned a living through rather atypical jobs. The hard career of the clandestine author was not his only activity; he was also among those that were referred to as “givers of counsel”.

He confirms it himself in his Memoirs of Monsieur d'Artagnan :

“There were men at the Court for whom it was the sole source of subsistence, and they lived so well on it that they could not understand why it did not make others desire to imitate them.”

As Jean Lombard explains:

“The small-time earners of this industry limited themselves, for example, to telling a friend, in exchange for compensation, which commission was likely to soon become available; but the more daring among them worked on a national scale, if one could call it that, by proposing to the king the creation and exploitation of new commissions; in this case, the privileged intermediaries, who had access to the minister Pontchartrain, were financiers and ladies of the Court.”

It seems that this activity did not bring him the revenues that he had hoped, because 1693 finds him in a dry spell.

Writing proved to be his most reliable source of earnings, and he was not lacking in ideas on a variety of different subjects. Unfortunately, even if what he wrote could not be qualified as really subversive, he was arrested in the same year 1693.

“From the authorities' point of view, the fault lay not only in the substance of his writings, but also in the circumstances of their publication: it was illegal to print a text without authorization, even more reprehensible than going through the Dutch book distributors, and totally unpardonable to be involved in the introduction and diffusion of such books in France.” Jean Lombard.

Courtilz was imprisoned in the Bastille for this “in the first chamber of the Tour de la Chapelle” and his fate depended on the warden. According to his writings, he did not like Monsieur de Besmaux, warden until 1698, at all, accusing the latter of enriching himself at the prisoners' expense. He also made the acquaintance of Monsieur de Saint-Mars, successor to Besmaux. We know about the circumstances of his detention thanks to his writing, notably the Memoirs of Monsieur J.B. de la Fontaine , but the mix of reality and fiction makes it difficult to form an accurate picture of events. Nevertheless, we do know that his stay was divided into two distinct periods: a period of real imprisonment followed by a period of “soft” detention which accorded him certain freedoms.

As Courtilz himself recounts:

“One should know that this prison is filled with two sorts of people: one sort is enclosed by four walls, never seeing anyone, except for the jailers who are given the name of key-holders… the other sort is accorded liberty by the Court and are locked up during certain hours… All those who have the Court's liberty send their valets into the city whenever they wish, besides the fact that they receive, without witnesses, anyone who wishes to come to see them.”

In the beginning, he had no visitation rights, then his wife received authorization to come see him, first exceptionally, then more and more frequently. Incredible, though, is the fact that he continued to write during his imprisonment and even to continue his journalistic activities, despite the strict control that he found himself under.

Again according to his written testimony, the prisoners developed certain tricks enabling them to communicate with each other and with the outside.

Courtilz was freed in 1699 and in the two years that followed, he published the following works:

- Memoirs of Monsieur d'Artagnan

- Annals of Paris and the Court

- Monsieur Colbert's Interview with Bouin

- Memoirs of the Marquis of Montbrun

- Memoirs of the Marquise of Fresne .

Numerous literary critics and biographers have claimed that the incorrigible Courtilz was imprisoned in the Bastille a second time for a period of nine years.

Jean Lombard, who scrupulously studied the prison's archives as well as other documents relating to activities at Courtilz's Le Verger property, does not agree with this assertion, as he underlines:

“One should rely on record, even at the cost of admitting certain shadows of doubt. We see two poles of attraction appearing in this later period of the life of Courtilz: the property at Le Verger, where, following the example of his ancestors, he occupies himself, with his family, with the different activities of the country gentleman, and Paris, where he is led invincibly by his tastes, his vocation as a writer and his often perilous obligations as a clandestine man of letters.”

However, he continued to publish secretly, despite his imprisonment in the Bastille and all the warnings he received.

And so, the Memoirs of Monsieur d'Artagnan appeared in three volumes in Cologne , under the editor Pierre Marteau. There are two editions: one from 1700 and another dated 1700 for volume I and dated 1701 for volumes II and III. Of course, “ Cologne ” is code for “ The Hague ”, and Pierre Marteau was certainly none other than his former printer Henry Van Bulderen.

Though protected by his political connections that kept him from returning to prison, and though his works sold relatively well, Courtilz was regularly followed, his activities under surveillance and literary critics were openly hostile to him “for reasons of morality or literary esthetics”.

Bayle writes of Courtilz:

“…he's a small individual without means, without fortune, and who apparently only writes all this just to sell it to the book distributors of Holland . Nevertheless, he must have some relation with the dilettantes of Paris who inform him of all the truths or falsehoods told by the chroniclers. One wishes that one would discredit in some newspaper this man's works, which infatuate an infinity of readers… One could doubtlessly prove the falsehood of the thousand claims that he advances. One has to admit that he spouts some rather curious and unusual ones, but what impudence to make three volumes of memoirs of Monsieur d'Artagnan of which not a single line was written by Monsieur d'Artagnan himself…”

From 1704 on, Courtilz's production began to decrease considerably and he retired to Le Verger where he led an existence of relative ease, all the more that his works sold relatively well. He loses his wife in 1706, after thirty years of a loving and harmonious marriage.

In the years that follow, we have little trace of him except that he manages to publish at least one of his older books legally: The Comportment of Mars . He also probably continued to write because three other books are published after his death.

Courtilz also remarries a third time in 1711, at the age of 67 and with a rather strange person: the widow of the book-seller Auroy who had once spied upon and denounced him!

This marriage would last less than one year, as Courtilz died on 8 th May 1712 .

His literary works

Faced with the perplexities of an author who remained anonymous all his life and who published clandestinely, many a biographer has attempted to inventory the literary work of Courtilz, an inventory that is far from complete.

It is Jean Lombard who has performed the most serious study of Courtilz and his work. After a long analysis of texts attributed to him and after rejecting those texts that had been attributed erroneously, Lombard arrives at a list of 36 texts authored by Courtilz:

Stories of Love and Gallantry (1678)

A Recount of Events in Catalonia during the Years 1674 & 1675 (1678)

A Recount of Events in Flanders and Germany during the Campaign of 1678 until the Peace (1679)

A New Anthology of Letters and Courtly Letters with their Responses on Various Subjects (1680)

The Conduct of France since the Peace of Nimègue (1683)

Response to the Book entitled the Conduct of France since the Peace of Nimègue (1683)

Memoirs Containing Diverse and Remarkable Events Occurring during the Reign of Louis the Great, the State if France upon the Death of Louis XIII and Her State at Present (1684)

A History of Illusory Promises since the Peace of the Pyrenees (1684)

The Romantic Conquests of the Great Alcandra in the Netherlands (1684)

Romantic Intrigues of the French Court (1684)

The Conduct of Mars (1685)

The Life of the Viscount of Turenne (1685)

The New Interests of Europe 's Princes (1685)

Ladies in the Natural State or Gallantry without Artifice under the Reign of the Great Alcandra (1686)

The Conquests of the Marquis of Grana in the Netherlands (1686)

Political Reflex ions by which We Demonstrate that the Persecution of the Protestants Is Against the Interests of France (1686)

The Life of Gaspard de Coligny (1686)

The Mercury of History and Politics (November 1686 – April 1693)

Memoirs of Monsieur L.C.D.R. (1687)

A History of the War in Holland (1689)

Political Testament of His Lordship J.B. Colbert (1693)

The Life of J.B. Colbert (1695)

The Best Tales from All the Courts of Europe (1698)

Memoirs of His Lordship Jean-Baptiste de La Fontaine (1698)

Memoirs of Monsieur d'Artagnan (1700)

Annals of Paris and the Court for the Years 1697 & 1698 (1701)

Meeting between Monsieur Colbert, Minister and Secretary of State, and the Famous Partisan Bouin (1701)

Memoirs of the Marquis of Montbrun (1701)

Memoirs of the Marquise of Fresne (1701)

The War in Italy or the Memoirs of Count D… (1702)

The War in Spain , Bavaria and Flanders or the Memoirs of Marquis D… (1706)

Memoirs of Monsieur de B…, Secretary to Monsieur L.C.D.R. (1711)

The Unfortunate Prince or the Story of the Chevalier of Rohan (1713)

History of the Marshal Duke of Feuillade (1713)

The Adventures of the Countess of Strasbourg and Her Daughter (1716)

Memoirs of Monsieur de Bordeaux (1758)

Upon reading this list of titles, on will notice that Courtilz concerned himself first with history, a recognized literary genre in the seventeenth century, before gradually turning his attention to fiction, which would be the all the rage during the century to follow. This shift drew the fire of the critics, Bayle among them:

“It's a pity that his man, having such fertile genius and the gift to write with such extraordinary ease and much vivacity, should not have found a more suitable way to employ his talents. If he had only adhered to the illustrious examples from Antiquity and the rules so nobly explained by so many masters of the historical art, he could have become a very good historian. But…he turns to fantasy all the topics he gets his hands on… He spouts fictions without regard for the chronology of events…”

Or even Niceron, who writes that Courtilz “has never bothered himself with the substance, nor with the form of his books, which are nothing more than historical novels, where the true, the false and the marvelous are blended.”

Courtilz's chosen literary orientation, which seemed to vex those who don't know how to classify or judge it, was, according to Jean Lombard, intrinsically related to the literary context of his time. The date of publication of this first book, 1678, remains a pivotal moment for the study of literature.

“With 1678 and the Peace of Nimègue, a new phase of our history begins. And the fact is that at that moment, and also in literature, although it the doors seemed to be closed to writers, other paths were also opened for them, especially in those genres for which a man like Courtilz was particularly well-armed.” One should also emphasize that Boileau and Racine were at that time the king's official historians.

Although it was not a very creative period for theater and poetry (the great playwrights of the seventeenth century like Corneille and Molière were already history), prose writing began to emerge onto the scene. The style appeared in many forms such as biographies, treatises, pamphlets, narratives, memoirs and … the novel: all the genres at which Courtilz excelled.

Journalism also appeared as a form that allowed expression, especially when it came to the unofficial gazettes that were printed in Holland and then sold in Paris . Courtilz found pleasure in this genre, too, and consecrated six years to journalism with his Mercury of History and Politics .

But it was memoirs that would interest Courtilz the most, because they offered a wide palette of possibilities, marrying reality and fiction while permitting the author to write in the first person. When the memoirs were not flattering for the character invoked, they could be considered more justly as pamphlets, and in this genre too Courtilz seemed to be in his element.

Indeed, one finds throughout the literature of the epoch numerous writings that played with the history or the biography of a particular figure by inserting fictional elements, much demanded by the public. Even the critics were fooled often and were not always sure to what extent they should put stock in these works. This was the case of the Memoirs of D.M.L.D.M. , for example, better known by the name of Hortense Mancini, Duchess of Mazarin and the Cardinal's niece. At first, the memoirs were believed to be truthful, then they were attributed to numerous different authors. This was also the case for the Memoirs of Monsieur de Pontis , of which the author's identity is uncertain, even if we can be reasonably sure that the author was not de Pontis himself.

This genre was therefore quite fashionable and offered some rather interesting literary possibilities.

“… whether it is historical or romantic fiction, around the year 1678 the gates are open for those who, interested in History or in love affairs, are in a position to insert into their work the rich reading experience or even their life, which is the case for Courtilz de Sandras.” Jean Lombard .

Courtilz has been criticized as lacking in rigor, of being a forger and even of having a certain obsession for the fantastic. In reality, his writing wove together reliable historical sources with hypotheses and events from the author's own life. He added to references gleaned from historical works a measure of romance or scandal to concoct a potion that was neither totally fact nor totally fiction and that attracted a loyal readership.

“It is in this way that, fully engaged in the business of living, free from any illusion and without excessive literary scruples, Courtilz de Sandras would accomplish his work with the confidence, vitality and independence of mind that so characterized him. Armed to respond to the possibilities that the literary context offered him, among others, he occupied, as we have just seen, any space that was free; but, attentive to the changes in his public's tastes, he would consecrate his greatest talent to the novel and its problems.” Jean Lombard .

It is by considering Courtilz as a novelist rather than as an historian that we can understand his work better and with more impartiality. We must also not forget one important detail: that is the experiences from his own life that he blends into the Memoirs of the lives of others. In this way the author makes his characters recount things that actually happened to him and this brings another, surprising dimension when reading his work.

“… [here] we are moving towards a novel that would emphasize the fragmentation of the individual and a questioning of his identity, in parallel with the scepticism and relativism of an epoch where the most solidly established certainties are beginning to falter.” Jean Lombard .

Finally, Courtilz put anecdotes before the main story and the lives of his characters are often only a pretext for numerous digressions. He loved the story within history, the kinds of stories that gave life to other transient characters and recounted events, both real and fictitious.

Nevertheless, and in spite of the criticism he suffered on this issue, Courtilz was a rather reliable chronicler of his time, and we can rely on his writing for his description of the historical events, the figures and the overall atmosphere of his century. He was an observer of the society of his time, which he represents with a fair amount of accuracy.

The great originality of Courtilz is the fact that he became a master in apocryphal memoirs, a genre for which he claimed credit, in which he was able to express himself freely and is not to be confused with the historical or romantic novel.

“… what characterizes Courtilz, in contrast to all his contemporaries, is his refusal to handle in a conventional way the genres that were in fashion, his desire to romanticize, without destroying it, the appearance of everyday reality, along with a picturesque style that reveals his personality (…) one's first impression when eh has read the totality of his books is that of having crossed the great century, led by a guide that could go anywhere (…) his heroes are nobles who do not question hierarchy, and socio-economic problems are not addressed in his work. But in giving first place to the individual's adventure, in showing the unfolding of private destinies against the backdrop of contemporary chronicle, in adopting an informal style in the form of first person narrative, Courtilz foresaw the dawn of an epoch where man would claim his independence from the constraints of society and history. Dominating a period in which writers often barricaded themselves behind formulas without a solution, he helped the novel, chiefly through his creation of apocryphal memoirs, find its identity. In giving it, particularly in the form of autobiography, the guarantee of truth that he had first looked for in history, he solved in his own way the problem of relationship between fiction and reality, and pushed along the way to autonomy a genre which became the ultimate form of expression for the modern man.” Jean Lombard .

Most interesting is how his works survive over time.

To begin with, Courtilz was largely used by authors of “authentic memoirs”, such as Saint Simon, who did not hesitate to “borrow” certain elements from him; which inspired Boislisle to say that their Memoirs “are neither more true, nor more infallible than the false ones and that Courtilz de Sandras speaks almost exclusively of his time and the personalities he frequented.”

Next, A; le Breton points out the debt that certain eighteenth century authors, such as Lesage, Marivaux and Prévost, owed to Courtilz, and he shows how his apocryphal memoirs “were the seed of the memoir-novels” of the following century.

The “modern” authors of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, too, discovered prototypes of adventures and heroes in some of Courtilz's characters. They found the prototype of the agile and audacious secret agent in the person of Rochefort ( Memoirs of M.L.C.D.R. ), the good pirate in the person of Gendron ( Memoirs of the Marquise of Fresnes ) and in particular the ultimate hero in war and love incarnated by d'Artagnan.

And so, we should render justice to Courtilz who was the first to turn his attention to d'Artagnan, preventing our hero from disappearing forever from History (with a capital H).

The Memoirs of Monsieur d'Artagnan

The “Memoirs” in question appeared in 1700, the very year that Courtilz was released from the Bastille. Their 1800 pages are divided into three volumes and constitute the author's most important literary work.

The book did not attract too much attention from Courtilz's contemporaries, judging from the criticism and the number of editions sold.

It tells the story of a figure that was both real and known by all. The book contains, much as Courtilz's numerous other books, a story line consisting of a narrative of the hero's adventures, a number of side anecdotes and certain historical events as a backdrop.

Jean Lombard points out that many an editor decided –mistakenly—to cut these historical events out of the book and to only preserve the story of the hero. They had ignored the book's title that announced, in addition to the Memoirs of d'Artagnan, “numerous secret and particular events that took place during the century of Louis the Great”. As its title indicated, the book's subject was not only the life of d'Artagnan but also the history of that epoch, both of which were closely linked.

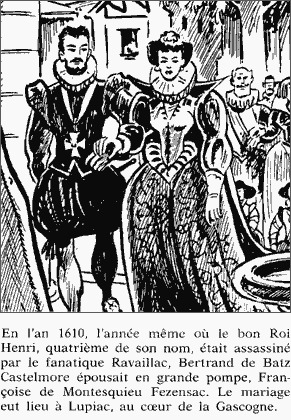

These “Memoirs” were written in chronological order and follow d'Artagnan from his birth in Gascony to his death in Maastricht all while citing events from French history. This, of course, did not leave the author a lot of room to exercise his imagination.

The anecdotes are also probably authentic at some level, though, as is often the case in Courtilz's writing, the anecdote was not necessarily experience by the characters cited in the book. One could consider the book as based on fact, if not entirely factual.

Predictably, the text also includes some autobiographical elements from the author's own life. For example, the narrator's professed enmity against Besmaux, the warden of the Bastille and a friend of the real d'Artagnan, or against Bussy-Rabutin, more accurately reflects the feelings of Courtilz than those of d'Artagnan.

In addition, Courtilz introduced romantic and psychological elements into his narrative that present some interest and would later be borrowed by Alexander Dumas and “translated” into a more lively style.

“And so, Courtilz gradually forged the path for an authentic fictional realism, founded on psychology and even, exceptionally, poetry. But it must be pointed out that, around 1700, his was a considerable contribution to history, in regards to the choice of his heroes as well as by a storyline consisting of a succession of known events.” Jean Lombard .

One should therefore read these “Memoirs” while keeping all these elements in mind.

These memoirs are not entirely faithful to the life of the real d'Artagnan, especially if one considers the romantic touches and diverse anecdotes that season the narrative, but they do paint a true portrait of the main character and the social and political context of that time. One should not forget either that Courtilz had also been a musketeer in the First Company at the very same time that d'Artagnan was its commander. Her therefore knew his character and certainly shared some moments with him, considering that the Company of Musketeers was a close-knit, elite club.

Although these “Memoirs” did not make much of an impression when they were published, it would nevertheless be reprinted more than any other of Courtilz's novels.

“In addition to Alexander Dumas' famous novel, these so-called “Memoirs” seduced Victor Hugo, who thought them to be authentic and particularly enjoyed the episode of Milady and his chambermaid. It was from the lost years of the nineteenth century that people began to take a renewed interest in d'Artagnan. In 1896, an anonymous, condensed version of the Memoirs in three volumes appeared in Paris . This is followed by English translations in 1898 and 1899. There would also be an adaptation in German in 1919 and a translation into Italian in 1945. In 1928, Gerard-Gailly published an abridged version of Courtilz's book, reissued in 1941. Also in 1928, appeared a Life of d'Artagnan by Himself . The work of Gerard-Gailly inspired another book in the same genre, “adapted from the narrative of Gatien Courtilz de Sandras”, published in 1947. Raymond Demay, in turn, “edited” the Memoirs of Monsieur d'Artagnan in 1955. G. Sigaux followed suit in 1965; the following year, it was the book-dealer Jean de Bonnot and, in 1979, Jean Michel Royer. Finally, the ultimate consecration, we should dare say, d'Artagnan is also the hero of a graphic novel adapted not, as one would imagine, from Dumas' novel, but rather from that of Courtilz, entitled D'Artagnan, His Real Life by Liquois, Adapted from the Authentic Memoirs written by Courtilz de Sandras .” Jean Lombard.

The least one can say is that the Memoirs did not attract indifference, perhaps thanks to, rather than in spite of, the subtle blend that married historical narrative and adventure.

As A. Jal writes in his Critical Dictionary of Biography and History :

“The Memoirs of Monsieur d'Artagnan are among the numerous works by Gatien Courtilz de Sandras, that writer who always blended history and the novel, to such an extent that it is difficult to separate one from the other in any of his historical works. What confidence can we place in the “Memoirs” of d'Artagnan? Assuredly, all is not invention; history rubs elbows with fiction, but she often loses herself in this association.”

Bibliographical references

- Courtilz de Sandras, Gatien – Mémoirs of Monsieur d’Artagnan – Mercure de France – 1987

- Gérard-Gailly, E. – édit. Mémoirs of Monsieur d’Artagnan – H. Jonquières – 1928

- Le Breton, André – A Forgotten Novelist : G. Courtilz de Sandras – in Revue des Deux-Mondes – 1897

- Liquois – D’Artagnan – Tome I et II – Les grands succès de la BD – édition PRIFO – 1977

- Lombard, Jean – Courtilz de Sandras and Criticism of the Novel at the End of the Great Century – PUF 1980

- Woodbridge, B.M. – Gatien de Courtilz, Lord of Le Verger: A Study of the Precursor of the Realist Novel in France – John Hopkins Press et PUF – 1925