The chateau of Mansencôme (or Massencôme), situated in the center of the village of the same name, dominates the valleys of the Baïse and Osse rivers from its promontory of 175 meters elevation.

The chateau of Mansencôme (or Massencôme), situated in the center of the village of the same name, dominates the valleys of the Baïse and Osse rivers from its promontory of 175 meters elevation.

The castle’s very name refers to its privileged situation: mas, meaning “habitation”, and côme, derived from the word coume (valley).

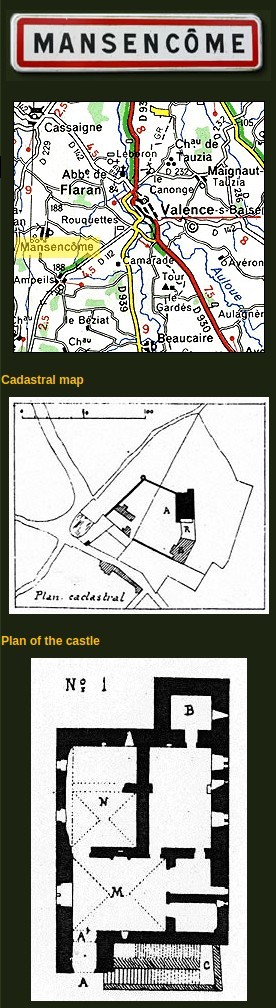

Mansencôme is characterized by the same architecture typical of other Gascon chateaux, with a large rectangular dwelling of two stories and two angular towers at either end, of uneven size.

The castle bears similarities to that of Tauzia: the same rectangular form for the main part of the edifice, squared towers, thick walls (an average of 130 to 140 cm thick), and the manner in which the interior is disposed. In contrast to its twin, which lay within English territory towards the end of the thirteenth century, Masencôme, situated in Armagnac, has always been a part of France.

As Philippe Lauzun writes, If they were not situated in opposing camps, one would think that they had had the same architect, as if he had condemned them, if not to serve the same cause, at least to oppose each other with the same means of attack and defense in time of war.

The promontory from which the castle rises is a remarkable observation point in that, in addition to dominating the valleys below, it also permitted surveillance of enemy lines and visual communication with other allied posts. Hence, the castle occupied a strategic position. It was probably built in the thirteenth century.

Mansencôme is also unique in that it is the exception to the rule that says that most Gascon chateaux possess neither moat nor rampart. This castle was indeed once surrounded by a polygonal wall, but that seems to have been more of an enclosure than a defensive perimeter, typical of edifices whose primary purpose was one of observation. Part of the wall has since disappeared.

Although conceived, like other chateaux of the region, to house a small garrison, Masencôme stands apart for its imposing size. However, we do not know if the castle’s seigneurs actually took up residence within her walls. Indeed, and despite successive remodeling over the centuries, the main part of the structure does not present the characteristics of a dwelling place. The absence of any opening on the ground floor or on the first floor and the lack of any fixed stairway lead us to conclude that the castle did not serve as a residence.

Philippe Lauzun affirms that only an addition linked to the main structure by a wall, and constructed in the fourteenth century, bears any visible traces of habitation. This would seem to prove that the seigneurs of Lasseran, the owners of Mansencôme, did not actually live at the site. Indeed, they possessed other, more sumptuous residences and only built this annex, much more practical and pleasant to live in than the dark fortress, for their personal convenience and for those short periods when they were obliged to visit the region.

During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Mansencôme was hardly occupied by its owners at all.

It was not until the castle’s new owners restored it in the nineteenth century that it became more … habitable. It is for this reason that we can now see transom windows on the castle’s exterior. But the restoration project must have been too expensive or poorly designed, because the work was never completed and the castle was abandoned yet again in “an unachieved state of shoddy transformation”.

Despite all the remodeling that has changed its appearance, Mansencôme remains a beautiful specimen of Gascon architecture from the end of the thirteenth century. As René Caïrou says, “in the absence of any military value, it nevertheless has a military bearing and a density of defensive features superior to any that we see elsewhere; only the Chateau Sainte Mère can rival it.”

The seigneurs of Mansencôme

According to Philippe Lauzun, “It is at the end of the thirteenth century, and precisely during the epoch that coincides with the castle’s construction, that we see the Lasseran family qualified as seigneurs de Massencôme.

Garcie-Arnaud de Lasseran, seigneur of Massencôme, Labit, Puch de Gontaud, Monluc, etc… had a daughter, Aude, who married Odet de Montesquiou. Clauses in the marriage contract stipulated that the children born of this union should carry the name and blazon of the bride’s father, that is Lasseran-Massencôme (…)

Aude was her father’s sole heir and gave the lands of Massencôme to her oldest son, Guillem, and the lands of Monluc to her second-born son, Guillem-Arnaud. The latter became head of the branch from which descended the famous Marshal Blaise de Monluc.”

Like many other seigneurs of Gascony, the Lasserans played an important role in the region’s military history.

-Already in 1356, a certain Manaud de Lasseran distinguished himself at a young age in the wars between France and England.

-In the fifteenth century, Isabeau de Lasseran is named heiress of Massencôme over her brother and marries a Seigneur de Poyanne. This new branch went on to enjoy military glory. Charles de Poyanne, the new master of Massencôme, served valiantly in the King’s armies during the Wars of Italy.

In the same manner as with the first heiress, Aude, the children born of this marriage with Poyanne would all carry the name Lasseran-Massencôme, ensuring that the family name survived up to the Revolution.

-A few years later, Jean-Alexandre de Lasseran, seigneur of Massencôme, served with distinction during the Wars of Religion, participating in a spectacular battle at Mirande. For, Henry of Navarre had fled his court in 1577, at the beginning of his fight against the League. He tried by every means possible to rally the Gascons to his cause and, after a bloody combat, finally took the town of Mirande with the help of a few local lords, including the Chevalier d’Antras and the Seigneur of Massencôme.

In his Memoirs, Jean d’Antras wrote: “Those inhabitants who were respected as being loyal subjects to the king did not lose anything. In this way Monsieur de Massencôme and myself rendered them service; we must also aid friends and neighbors in need, because we should remember with the ancients, pugna pro patria, and it is thus that we must live in this world.”

-In 1656, at his palace in Fontainebleau, King Louis XIII issued patent letters of nobility in which he established the Barony and Lordship of Massencôme: in recognition of the numerous services rendered by François de Massencôme in his commission as governor of Marciac, during which he aided in the siege against those of the so-called reformed religion, and also for the services of his son, Bernard de Massencôme, as an officer in the regiment of Saintonge, and also in memory of the service of their predecessors and even that of the Marshal Blaise de Monluc.

Toward the last half of the seventeenth century, the Marquis of Maniban, neighbors to the fief of Massencôme, began to acquire certain rights over this seigneurie, and ended up possessing all the Massencôme lands by the end of that century. And so, after five centuries in the same family, Massencôme fell into “foreign” hands.