An extract from the article “The King’s Musketeers and their arms” by Clement Bosson, in the Gazette des Armes (N° 42, October 1976), reprinted here with the author’s permission.

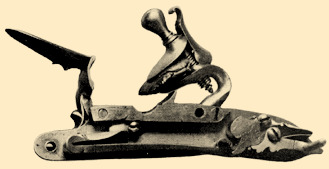

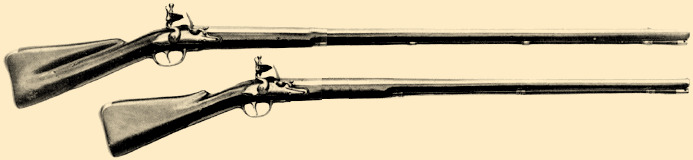

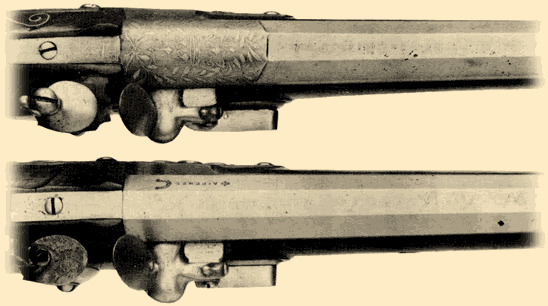

The musketeers of the company of Louis XIII were armed with muskets –almost certainly a matchlock musket, not as fragile for the battlefield as the wheellock– and, of course, with a sword and a pair of pistols packed in the saddle. Father Daniel writes in his History of the French Militia, completed around 1721: “… The corporals and second corporals…carried rifles. The musketeers also had army rifles going back a number of years and only carried their muskets in military reviews. Today, they don’t use the musket at all.”

In 1657, they still carried the matchlock musket.

Here’s what we can read in the Journal of a journey to Paris in 1657-1658:

“On the 19th of January 1657, we went to see the King enter [Paris] by Saint-Antoine’s gate with his 120 new musketeers who are also his body guard … they carry muskets and attach the fuse to the harness behind the horse’s two ears.”

The matchlock musket proved quite accurate in the hands of the musketeers. Le Pippre, whom we have already cited, relates an episode of the siege of Dunkerque by the royal army under the command of Turenne, when Condé and Don Juan of Austria, at the head of the Spanish army, tried to rescue the city (June 1658):

“…The Prince of Condé sent the cavalry forward through a breach in the dunes where they could only advance at twenty abreast. The musketeers stopped them with musket fire and threw them into disarray and then continued to harass Monsieur the Prince’s troops with a well-aimed barrage…”

At what time did the rifle replace the musket?

We remember that, in 1671, the King created a regiment of riflemen, an elite corps attached to the artillery and armed with flintlock rifles to replace the muskets. We can suppose that the musketeers, also an elite corps, received the new weapons at the same time. Alas, it is impossible to have any precision when it comes to the armament of the [king’s] military house, as this establishment fell not under the war administration but under the king’s house. The archives of the latter have never been found.

What was the appearance of the musketeer’s sword at the time of the creation of the corps?

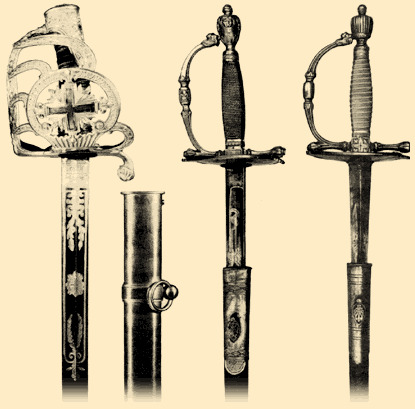

Although we haven’t received any objects whose attribution was certain, we can make an educated guess, without the risk of erring too seriously, with a study of a document of the epoch, Le Maneige royal, written by Antoine de Pluvinel (1555-1620), director of the king’s stables. This work, with a number of illustrations by Crispin de Pas, depicts riding lessons and the nobles who participated. Their swords [the epee] are what we call “branched”, with a heavy pommel either round or in olive wood, a guard[the lower pat of the hilt, protecting the sword-wielder’s hand], the branches straight or curved, several oblique guard rings, a pas-d’âne [rings between the guard and the blade, supporting the guard] , the side ring joining the base and the rings or branches of the contra-guard. The blade is broad and strong, because the musketeers always charged with their swords –and not with the bayonet—as attest a number of texts citing their heroic conquests of fortified positions. This book, published in 1626, is therefore a valuable reference for the musketeers’ sword at the time they joined the king’s guard in 1622.

It seems that the branched epee, probably simplified compared to that in use in 1622, was used by the musketeers for most of the seventeenth century. A fresco by one of the old rectors of Invalides, attributed either to Adam-Frans Van Der Meulen (1632-1690), in collaboration with his apprentice Jean-Baptiste Martin (1659-1735), or to Joseph Parrocel (1646-1704), depicts a group of musketeers at the siege of Ghent in 1678. One of these frescos was reproduced by Eugène Leliepvre. The sword sports a hilt with branches, somewhat rudimentary.

Toward 1680, it seems that the French cavalry was armed with a Walloon sword, with a broad blade, a guarding branch and two bridges consisting of iron sheets. A bridge linking the nerves of the contra-guard to the pommel formed a knuckle-guard. This weapon, too rudimentary, was probably not used by the musketeers.

What is the appearance of the musketeers’ sword at the end of the seventeenth century?

Let us try to find the answer by consulting a scholarly work completed in 1695: Memoirs of the artillery collected by Monsieur Surirey de Saint-Rémy, lieutenant to the grand master of artillery of France.

The author presents an imposing series of military weapons. In the category of swords and sabers, he stops at three sorts: one saber and two types of epees. The plank [in his work] shows these weapons: one is an epee with a wide blade and a large pommel, the principal guarding branch prolonged by a quillon de parade, the pas-d’âne above the coquilles. In sum, it’s the same epee that would later be called the musketeer’s sword and it appears here as a powerful combat sword.

Further, this sword is worn by the musketeers in numerous documents from the first half of the eighteenth century. However, it would receive its appellation much later and, it seems, for the first time in the text of a decree from 25th April 1767.

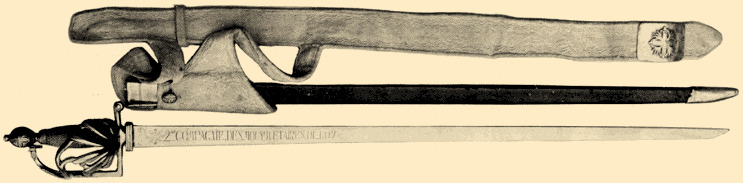

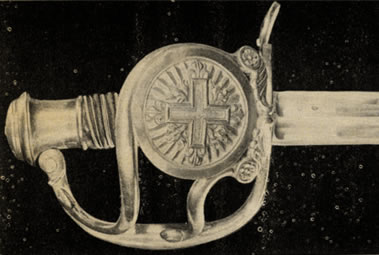

The moment they return to Paris, before the Hundred Days, the musketeers carry a saber different from that of the Ancien Regime. The hilt is composed of a guarding branch and of two or four branches on the sides with the musketeers’ famous motif in on the grip: the flaming cross in the form of the fleur-de-lis. The blade is straight or with a slight curve and has a length of 33 inches (89.3 cm).

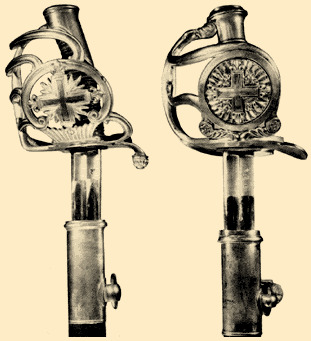

The swords that have been conserved, which are the oldest ones of the two companies, are those of the Christian Ariès collection and of the army museum at Salon-de-Provence (formerly of the Jean and Raoul Brunon collection). Christian Ariès replaced the “musketeer” models with these models from around 1759.

These epees with guards, with hilts in gold for the first company and in silver for the second company, culminate in a round, slightly flattened pommel with the cross of the corps engraved on each side. The blade is flat, resistant, 34 inches (92 cm) long by 14 lines (32 mm) wide, with a thickness of 4 lines (9 mm). It’s quite a powerful sword. And yet, at this time, the musketeers only served as guards or attendants.

The king’s military house lived its final hours of glory at the battle of Fontenoy on the 12th of May 1745.

The musketeers’ saber: a weapon as recompense

Barely one month after his entry into Paris, Louis XVIII, provides for the establishment of a commission to attribute merits, among others, to those who participated in royalist movements against the revolution. The purpose was to recognize the spectacular feats of the armies of Brittany and Lower Normandy and of the Royal Army of the West.

The royal commission, in its session of 30th July 1816, adopted the types of weapons of merit provided for (epees, rifles and sabers) and notably for “… the lower officers and soldiers … having served in the cavalry, a saber conforming to the model of the sword of the king’s musketeers, to which we will substitute the cross in between the branches of the hilt with the coat of arms of France.”

These were the arms of the second company (silver guard), manufactured by the workshops of Versailles during the reconstitution of the corps, and removed from the palace of Versailles, where they had been stored, to be modified. The cross was replaced by a medallion bearing the arms of France against a background of flags. On the blade, the inscription: “Long live the King”. The arms of merit were awarded to those concerned on the 25th August 1824, the feast day of Saint Louis.

Thus ended nearly two centuries of history and 123 years of military glory.