A Successful serialized novel

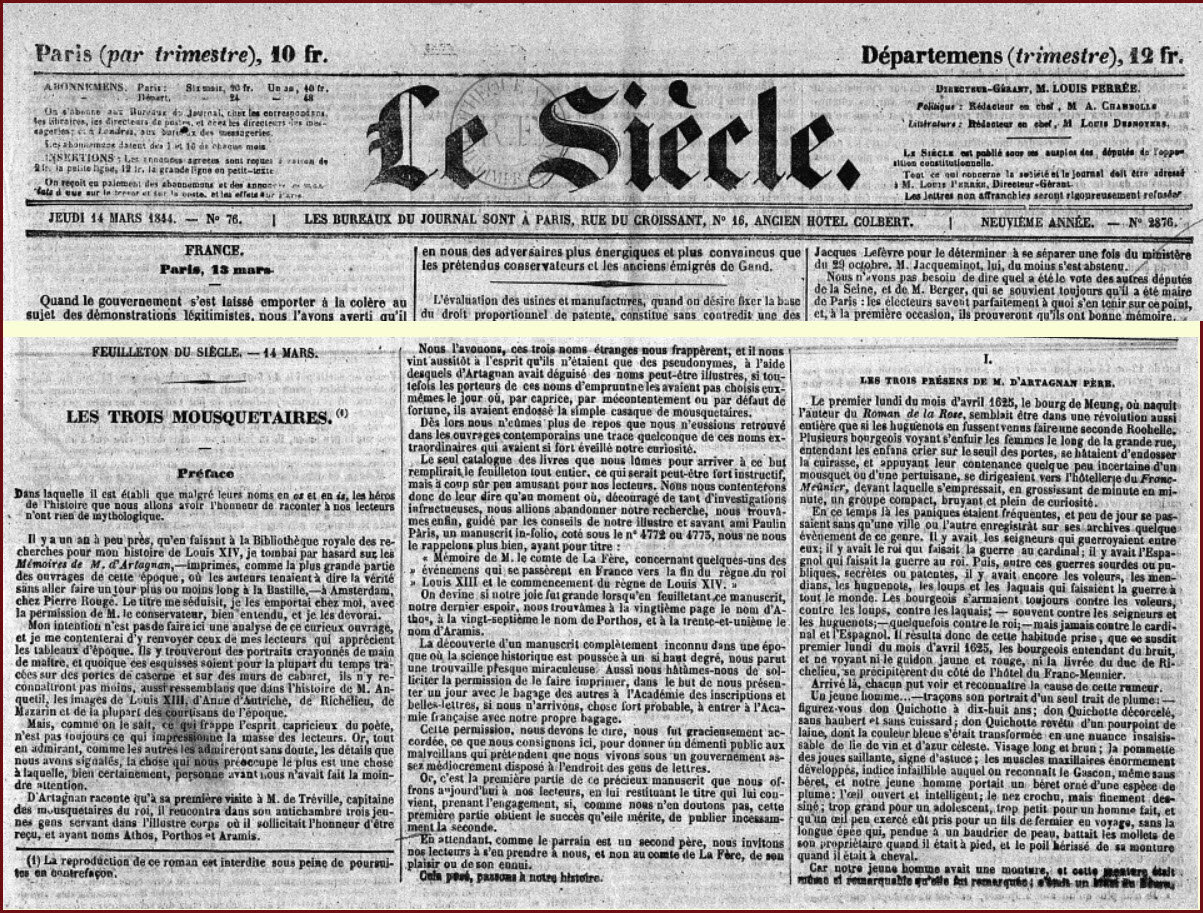

The story of The Three Musketeers was published as a serialized novel a famous newspaper of the epoch, Le Siècle , between 14 March and 14 July 1844 . The novel's first title was Athos, Porthos and Aramis until a journalist suggested that Dumas change the named to the title we all know.

Dumas is said to have answered, “I agree even more with your suggestion to call the novel The Three Musketeers considering that, as there are four of them, the title will seem absurd, which will guarantee the book to be a success.”

Actually, the title was not that absurd in light of the fact that Athos, Porthos and Aramis are the only three musketeers in much of the novel, d'Artagnan becoming a musketeer much later. However, the latter soon becomes the book's main character, and even the image of the ideal musketeer…

…the ultimate musketeer, whose personality eclipsed all the others, which would have justified a title like D'Artagnan and the Three Musketeers.

Charles Samaran

Dumas certainly wanted it that way because he begins his novel with d'Artagnan leaving his native southwestern France , armed with his sword, letters of introduction and his fiery spirit, like all the Cadets of Gascony at that time. He is the character that the reader meets first, follows to Paris and then in all his adventures that lead the hero from the French court to England, encountering every imaginable danger but supported by the solid and amazing friendship of his three companions.

The stakes were high for Le Siècle in publishing the novel. The newspaper was trying to compete with the success of Eugene Sue's serialized novel The Mysteries of Paris , which had appeared the previous year in La Presse .

The newspaper's hopes became reality when The Three Musketeers became a huge success. It was the third novel that Dumas and Maquet had conceived together and their first big success. From that moment on, Dumas would shift his emphasize from theater to novels.

It can be said that this novel had two successes, one as formidable as the other, first and most of all at the bottom of the front page of Le Siècle , then in the bookstores (…) No doubt, no other literary event, except the publication of Les Misérables , had ever absorbed a people's life to such a degree and with such unanimity (…) the story of d'Artagnan made all others ignored, forgotten (…) All France was under the spell of the musketeers.

Henri d’Almeras

Not only that, but the novel's success was also universal in the sense that it swept through every social class, Paris and the countryside, men and women alike and quickly crossed frontiers and oceans to reach other countries…

If another Robinson Crusoe exists somewhere out there on his deserted island, rest assured that this lonely castaway is at this very moment reading The Three Musketeers underneath his parasol made of parakeet feathers.

Méry

In 1849, Dumas and Maquet together adapted their novel to the stage under the title The Musketeers' Youth . This was followed by two sequels to the novel: Twenty Years After and The Viscount of Bragelonne .It seems that upon rereading his novel The Three Musketeers at the end of his life, Dumas found it quite good, better even than The Count of Monte Christo . Of all the characters that Dumas had created, it was these (the Three Musketeers) that he preferred. From the beginning, he identified with them, but most of all with the most complete, the most popular, the fourth, his best friend… And Dumas was d'Artagnan transformed into a writer and whose tireless pen preserved the glint of the sword.

Henri D’Almeras

Dumas-D'Artagnan: that was his name.

Jules Janin

Alexander Dumas’ sources of inspiration

I am in the habit of doing very serious research on the historical subjects about which I write.

I am in the habit of doing very serious research on the historical subjects about which I write.

Alexandre Dumas

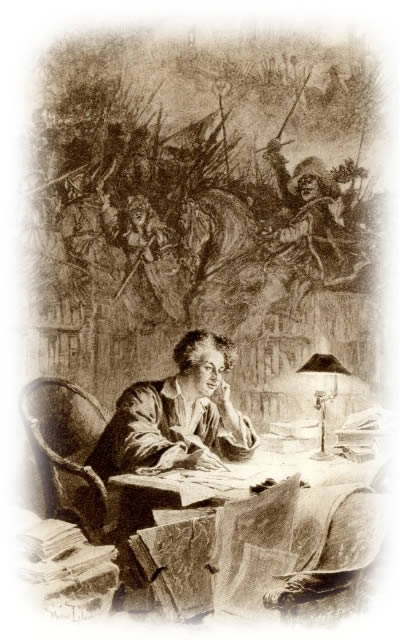

Dumas made d'Artagnan's acquaintance at the library of Marseille, where he had come to borrow a book entitled Memoirs of Monsieur d'Artagnan by Gatien Courtilz de Sandras. These apocryphal memoirs were to be his primary source of inspiration. There he discovered his future hero, but also many other protagonists, amazing adventures and anecdotes from the epoch that he would use and transform with his verve and his vivid imagination.

Did he know that d'Artagnan had really existed? Certainly, because Dumas and his collaborators, such as Maquet, did research, read a number of historical works and, notably, the memoirs of figures like Mademoiselle de Montpensier or Saint-Simon, who wrote of the real d'Artagnan.

More, at the same time Dumas also wrote an historical epic on Louis XIV and His Century in which he related the event of Fouquet's arrest without omitting the role that d'Artagnan played as the former's jailer.

That said, he had to borrow from Courtilz what the history books had not yet written about the musketeer: his life.

Although already fictionalized and arranged by Courtilz, the apocryphal memoirs of d'Artagnan present a chronology of the protagonist's life that Dumas would go on to use on a number of occasions. One episode borrowed from Courtilz, that of the beginning of his hero's story with his departure from Gascony, would be reprised by numerous swashbuckler novels that presented a hero –Gascon—leaving the countryside of his origins for Paris on his steed.

Dumas then culled from the Memoirs such adventures as the hero's quarrels with the Count Rochefort (whom Courtilz names Rosnay), his arrival in Paris where he meets Athos, Porthos and Aramis, his love affaires (Madame de Bonacieux is called Madeleine in Courtilz's book), not to mention amusing anecdotes like the story of Porthos' baldric (worn by Monsieur Besmaux in the book by Courtilz). He also found his schemer in Courtilz, the troubling Milady, whom Courtilz had styled as the enigmatic Miledi X. With d'Artagnan and Milady, Courtilz also “gave” Dumas the ideal duo of Good and Evil, one of the cornerstones of the serialized novel of the epoch.

Courtilz de Sandras' contribution to the writing of the Three Musketeers didn't stop with the Memoirs of Monsieur d'Artagnan . Dumas had also read his memoirs of the Duke of Rochefort, or Memoirs of M.L.C.D.R. In the latter he found a detail that he would exploit rather brilliantly: the custom of tattooing one's shoulder with the fleur-de-lis, once reserved to people condemned to service in the galleys of ships. Dumas would give this distinctive mark to his character Milady.

The story also had to offer exciting ups and downs and keep the reader's interest. And so, Dumas added a crime subplot, spiced up with the intrigue of an illicit affair, with the episode of the Queen's aiguillettes (an aiguillette is a metal tag or ornament at the end of a shoelace or ribbon). To bring in these extra elements, he read other memoirs, such as those of the Count of Brienne, Madame de Motteville, François Bertaut or La Rochefoucault, which directly inspired his love story between Anne of Austria and the Duke of Buckingham.

As far as the Queen's aiguillettes were concerned, this story must have started with the Memoir in Service to History and Polite Society in France by Roederer, or one of the latter's comedies entitled The Aiguillettes of Anne of Austria , which tells the story of a missing jewel very much like the episode one can find in The Three Musketeers and that is a centerpiece of the intrigue involving Anne of Austria, Richelieu and the Duke of Buckingham. Roederer, in turn, found his inspiration in the memoirs of the Count of Brienne as well as those of La Rochefoucault.

According to Dumas' biographers, we can also add to his list of sources the memoirs of La Porte , the Historiettes of Tallement des Réaux, the Memoirs of Bassompierre, the Essay on the Habits and Customs of the Seventeenth Century by F. Barrière and Richelieu 's Memoirs .

Finally, one should not forget the imprint left by Auguste Maquet, who collaborated closely with Dumas in the writing of the Three Musketeers , and whose own grandfather is thought to be the model for the character of Porthos.

However, all these documents, all these anecdotes and intrigues that inspired this story are not enough to make a successful novel. It was necessary to assemble all these little tidbits, render them coherent, interesting and lively and to space them apart to season the weekly episodes. It is there that Dumas' genius enters the picture and transforms this sack of anecdotes into a brilliant saga, the novel that we all know.

Three writers of differing qualities collaborated in the in the making of the Three Musketeers: Gatien de Courtilz de Sandras for the scenario and the intrigue; Maquet for the story outline, the first draft and the book design; Alexander Dumas for the animated narrative and dialogue, the color, the style, the breath of life.

Henri d’Alméras

True historical fiction

As a literary genre, The Three Musekteers could be considered as an historical novel, as well as a serialized novel and an adventure novel.

As a literary genre, The Three Musekteers could be considered as an historical novel, as well as a serialized novel and an adventure novel.

The historical novel was all the rage in the nineteenth century and, like the serialized novel, it originated in England . It was Walter Scott who was the father of the historical fiction genre; his books made it across the channel to France between 1815 and 1830.

This marriage between history and fiction, while obviously inspired by real history, often plays with the facts, blurring the lines between fiction and reality. Added to the mix is a little romantic subplot, to spice up the story a bit.

The Three Musketeers perfectly fit the mold.

From a strictly historical point of view, the novel obviously presents numerous inconsistencies in the description of people, places and events. But the novel only gives us an historical framework; it does not claim to be a course in history, as Dumas himself writes in his Memoirs :

I have always recognized history's admirable indulgence in this regard; she never leaves the poet in difficulty. Thus, my approach to history is strange. I begin by devising a fable; I try to make it fantastic, tender, dramatic, and, once the right formula of imagination and heart has been found, I look to history for a framework to put it in, and history has never failed to provide me this framework, so exact and so appropriate to the subject, that it seems that it is not the frame that was made for the painting, but rather that the painting was made to fit the frame.

With this postulate as our point of departure, one notices that numerous events and characters in the novel are close to reality, starting with d'Artagnan, whom millions of readers consider to be nothing more than an invention of Dumas.Not

only is the character not a figment of imagination, but the man could already be considered as a heroic figure for his time. Dumas' hero and the real d'Artagnan share many common personality traits. They are both loyal, true, courageous and enterprising, prepared to risk themselves to save the monarchy.

Dumas' d'Artagnan saves the queen's honor while the real one was an unconditional bulwark of royal power, Anne of Austria included. With one difference: the real d'Artagnan never opposed Richelieu , because it was under Mazarin and Louis XIV that he rose through the ranks to become Lieutenant-Captain of the Grand Musketeers. Dumas, in fact, moved events back fifteen years to serve his story.

Rather, it was Monsieur de Tréville (or Troisville) who had been Lieutenant-Captain of the Musketeers under Louis XIII and who found himself so often at odds with Richelieu . He was originally from Béarn, loved by his men, a straight-shooter with a strong personality, unconditionally devoted to the cause of the king, of whom he was a favorite. His musketeers and the Cardinal's guards were constantly competing against each other. Dumas' character is more or less faithful to the real figure.

Athos, Porthos and Aramis refer to actual historical figures, who happened to be musketeers. The first of the three, whose real name was Armand de Sillègue, took the name of his village –Athos—near the town of Sauveterre-de-Béarn . He was Monsieur de Tréville's nephew and became a musketeer in 1640.

Isaac de Portau, alias Porthos, originated from Pau (capital of Béarn) and became a musketeer around 1643.

Aramis' real name was Henri d'Aramitz; he was also a Béarnese man, from the valley of Barétous , and a cousin of Tréville. He, too, became a musketeer around the year 1640.

Dumas found these exotic-sounding names irresistible and wished to make them the title of his novel. Was it because, according to Tallemant de Réaux, the names of the Béarnese musketeers were so difficult to pronounce? Indeed, these three figures played an important role in the novel's success even if they posed some problems for the editor, who pointed out in the book's original preface that “despite their names ending in OS and IS, the heroes of this story that we have the honor of presenting to our readers are in no way figures from mythology.” But, of course! They were all Gascons…

Indeed, the native region shared by these musketeers, including d'Artagnan, would provide Dumas with a solid base for the fraternity that united them—a brotherhood that has become legendary. The “all for one, one for all!” of legend has its roots in a tangible reality, that of this grand fraternity of Gascons that found itself in Paris among all the other musketeers and soldiers of the kingdom.

The Gascons were famous not only for their strong character and their bravery, but also for their clannish tendencies which permitted them to help and support one another. They were formidable soldiers, respected and feared for centuries, larger than life personalities known for their generosity and their enthusiasm. These were the famous “cadets” of Gascony who provided rich material for fiction writers of the nineteenth century, from Dumas to Gauthier and Rostand (of Cyrano de Bergerac fame).

In fact, we even find Gascons in Dumas' other works, such as in The Forty-Five or The Dame of Montsoreau , with their delicious accents, their conviviality and their sincere loyalty.

Dumas must have been well familiar with the famous Gascon spirit, because even the pact that he has his musketeers create has historical precedent. An association of Gascon gentlemen actually existed in the fourteenth century, the members of which swore an oath of unconditional mutual aid. This oath could be summarized by that magic formula “All for one and one for all”.

As far as the musketeers' daily life was concerned, it was pretty close to the scenes described in Dumas' novel. When they weren't in the field of battle, the real musketeers were known for their sometimes deadly duels, their vanity and somewhat lacking scruples and their frequent love affairs. They were combative and often ignored orders forbidding them to duel among themselves, and although discipline was strict within the First Company of Musketeers, they were known for their excesses in between campaigns, “admirable in war, unbearable in times of peace”. Some of their number acted as if they owned the city of Paris and tried to obtain special privileges while making mischief and spreading disorder. It is true that the slightest misunderstanding or unpleasant word would make them reach for their swords. Dumas certainly did not exaggerate this point, as duels were frequent and often disproportionate to the supposed provocation.

For lack of anyone better, the musketeers fought among themselves, and they would have even fought the devil himself, but they much preferred to tangle with the Cardinal's guards, their favorite adversaries.

Henri d’Alméras.

It is easy to understand the jealousy that the musketeers had for Richelieu 's guards . For, they were not compensated as generously as the latter, and it was common for a musketeer to live on the purse-strings of a wealthy mistress.

Whether bourgeois, like the mistress of Porthos, or “grandes dames”, like Aramis' mistress, these women were great admirers of these young and valiant soldiers. Boileau, in his famous satire of the institution of marriage, paints a picture of one of these female admirers, “smitten by a cadet, intoxicated by a musketeer”, and Mademoiselle de Scudéry , not without her reasons, disguised the god Cupid as a musketeer, whom she knew only from hear-say:

Who is this little musketeer,

So skilled in arts of sword and spear

And even more in the art of seduction?

The enigma offers a solution:

For it is Love, there is no mystery,

(…) And that is why so many musketeers got their uniform for nothing. And when Porthos prevailed upon the procurer's wife, not without difficulty, to equip him from head to toe, he found this present appropriate, quite natural, and he probably felt that he had merited it.

Henri d’Alméras.

By choosing the reign of Louis XIII as his backdrop, Dumas was sure to have an historical context that would easily lend itself to a picaresque novel. The discord that reigned between the king and his queen, Anne of Austria, was profound, and the ambiguous role played by Richelieu probably only served to aggravate the situation. This trio thus offered a perfect backdrop for a story full of intrigue. So, too, the very real friction between Richelieu's Guards and the King's Musketeers gave rich possibilities to the novel's four protagonists.

The novel's charm resides in its skillful mix of reality and pure invention and its ability to render believable all that is false and improbable all that is true.

The rapport that Dumas entertained with history rested entirely on this difficult and marvelous exercise in style, without leaving out the most important…

“…the effort undertaken by Dumas to reflect on history, and to find coherency and meaning, amidst the abundance of chronicles and memoirs.”

Claude Schopp.

“The mission of the historical novel is to erase the boundaries between the real and the imagined, to establish a veritable continuity between the two and, in the end, to mix them up.”

Daniel Compère.

Finally, and particularly as it concerns The Three Musketeers , Dumas has done history a great service. First, he prolonged with flair the work of Courtilz by preventing d'Artagnan from disappearing from history. Next, he gave life to that elite corps known as the musketeers. Strangely, these men –d'Artagnan in particular—who had been the cream of the King's House in the time of Louis XIII and Louis XIV, who served their kings with uncommon valor and who were so feared on the field of battle, could have easily slipped into oblivion.

With the Revolution and the disbanding of their company in the eighteenth century, the musketeers were swept away along with other symbols of royal power. More, the abnegation and sense of honor of their most glorious Lieutenant-Captain –d'Artagnan—were such that the latter never sought out fame. His biographers had the colossal task of rewriting his true story and rediscovering his trace.

Alexander Dumas can be credited with constructing this wonderful bridge between the centuries, the bridge of memory. He gave us a fictional hero who supplanted the real one, but who shared all the same attributes, thus paving the way for the rediscovery of the real d'Artagnan in the century that followed. A sleeping hero awaited his awakening.